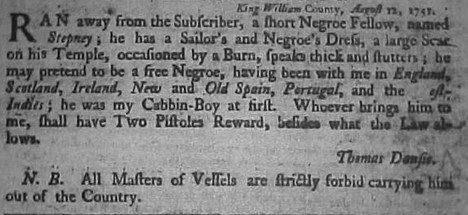

Stepney had seen a lot of the world. He may well have been born more than five thousand miles east of Virginia, for more than one-third of mid-eighteenth Virginia’s enslaved population had been born in Africa.[1] If that were the case, his oceanic travels had begun with the horrific Middle Passage, but thereafter his journeys had been above deck as a sailor, voyaging far beyond the Chesapeake to different parts of the British Isles, to Spain and Portugal, and to the West Indies and to Spanish colonies, all by his mid-twenties. We know this because of a series of advertisements placed by his enslaver, Thomas Dansie. In mid-July of 1751 Stepney escaped, and between August 1 and September 5 five advertisements appeared in the Virginia Gazette, several adding information about the young man and increasing the reward for his capture. Escaping from Dansie was inherently dangerous. Two years earlier the enslaver had advertised for a “Virginia born Negro Fellow, named Jack Spurlock” who had been absent for a year, promising a reward for his return “dead or alive.”[2]

Thomas Dansie hailed from London, and his widowed mother Mary still lived in Ratcliff, in Stepney in London’s East End. Surely the young enslaved man was named by Dansie in honor of the place he had come from, bringing comfort to the enslaver but demeaning the young enslaved man with an English place name rather than the name that his parents had bestowed upon him. Dansie was a ship’s captain who had spent years sailing all around the North Atlantic and Caribbean: newspaper reports of ship arrivals and departures reveal him captaining the Braxton on a voyage from London to Portugal to Virginia and back in 1738; the Albemarle between London and Virginia in 1739; and the Neptune between London and Virginia in 1745.[3] Having begun as a cabin boy Stepney might not even have been ten years old when he first started working aboard Dansie’s ships. He had likely spent more than half of his life aboard ship, and his “Sailor’s… Dress” identified his profession.[4]

By 1751 Dansie was about forty years old and he no longer captained ships on long and dangerous voyages. His familiarity with Virginia and the opportunities it presented had led him to relocate from London, and he had invested in a plantation as well as building a wharf on the Pamunkey River, which flowed into the York River. The wharf was about 40 miles from the open waters of Chesapeake Bay, and it provided nearby planters with the means of loading locally grown tobacco onto boats and smaller ships.[5] But while Dansie eased into a comfortable retirement in Virginia, it is likely that Stepney experienced the transition very differently. For years the young enslaved man had enjoyed the relative freedom of life and work aboard ocean-going ships. Crews were often ethnically and racially diverse, and while the work was challenging there could be a rough equality among men who depended upon one another on the open seas. As a sailor Stepney had quite likely enjoyed a measure of freedom and equality that all but evaporated when Dansie retired to his Virginia plantation. On deck or in the rigging, hundreds of miles from shore, or spending time in the taverns and markets of Lisbon or London, Stepney may often have felt more free than enslaved. But as an enslaved man in Virginia Stepney experienced a dramatic reduction of his relative liberty, for in the plantation society of the Old Dominion his life and work were more constrained than they had ever been.[6]

And so Stepney escaped. Dansie believed that the young man might well “pretend to be a free Negroe,” and his seafaring experience and professional clothing may have made this easier. It seems likely that Stepney escaped on a ship leaving Virginia for the British Isles, perhaps convincing a captain that he was indeed free and master of his own fate, and demonstrating his professional qualifications in his talk and actions. We know this because early the following year an advertisement for Stepney appeared in a London newspaper.

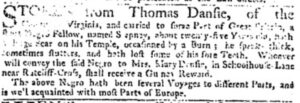

The new advertisement was similar to those Dansie had published in Virginia, adding more identifying features including the estimate that Stepney was about twenty-five years old, and that he “hath lost some of his fore Teeth.” Dansie reiterated that Stepney had been on “Voyages to different Parts, and is well acquainted with most Parts of Europe,” and the former ship captain was no doubt trying to communicate to other maritime men that just because Stepney might appear to be an experienced sailor did not mean that he was a free man. The other main difference in this advertisement was the notification that if Stepney was captured he could be returned to Dansie’s mother, Mary, in the East End district for which the young freedom seeker had been named.[7]

If Stepney had indeed made it to England it seems unlikely that he would have been recaptured. Although freedom seekers and enslaved people in London were often in danger of capture and enforced passages to the plantation colonies, there were more free than enslaved Black people in the metropolis, including a large number of sailors. His experience and his presumed immunity to the tropical diseases that killed so many White sailors would have made Stepney a sailor worth hiring. While other enslaved people named Stepney crop up in London and Virginia records, none would appear to have been this young man, who had almost certainly marked his escape by changing his name. With his escape and name change Stepney disappeared from our view, quite likely continuing his earlier life as a sailor, but now as a free man.

View References

[1] There were an estimated 100,000 enslaved people in Virginia in 1750, and the Transatlantic Slave Trade database reveals that an estimated 65,000 enslaved Africans were brought to the Chesapeake region in the 25 years between 1726 and 1750. See United States Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1957 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce, 1960), 756; Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, including estimates function, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database (accessed January 26, 2024).

[2] See “RUN away from the Subscriber… Stepney,” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), August 1, August 8, August 11, August 29, September 5, 1751. “RAN away from the Subscriber… Jack Spurlock,” Maryland Gazette (Annapolis), March 15, 1749. A pistole was a small Spanish coin made of gold, and was in 1750 worth a little less than £1. See John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600-1775: A Handbook (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 11.?

[3] “Enter’d in York River,” Virginia Gazette, May 5, 1738; “Yesterday arrived in York River,” Virginia Gazette, February 2, 1739; “Just imported… in the Neptune, Capt. Dansie, from LONDON,” Virginia Gazette, September 26, 1745.

[4] “RAN away…Stepney,” Virginia Gazette, August 29, 1751.

[5] For references to ships docking at Dansie’s wharf see, for example, “THE Adventure… now lying at Capt. Dansie’s, in Pamunkey,” Virginia Gazette, August 21, 1752, and “THE Snow, Frances… at Capt. Dansie’s in Pamunkey,” Virginia Gazette, September 22, 1752; “THE Ship RIALTO… now lying at Dansie’s wharf,” Virginia Gazette, June 20, 1766. In 1761 the Virginia Assembly empowered Dansie to operate a ferry from his wharf across the Pamunkey River. See “An Act to impower Thomas Dansie to receive Ferriages for transporting Passengers to and from the Causeway opposite to his Land, and for other Purposes therein mentioned” (1754), Virginia Acts, Boards of Trade and Secretaries of State: America and West Indies, 1752-1761,National Archives, CO 5/1396.

[16 We know Dansie’s age from baptismal records: see Thomas Dansie, baptism April 8, 1711, Christenings, Saint Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, 1710-1722, London Metropolitan Archives, 17.

[7] Mary Dansie appeared in various documents as the “widow of Thomas Dansie in Schoolhouse Lane in the hamlett of Ratcliff, including her late husband’s will. See deposition of John Merril, January 16, 1735, Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers—Justices’ Working Documents, London Metropolitan Archives, LMSMPS503140046; Will of Thomas Dansie, Mariner of Stepney, Middlesex, September 3, 1735, National Archives, PROB 11/673/5.