Did Penelope’s heart pound as she took shelter in the forest on the outskirts of town? Did she gasp for air as she tore through the nearby farmland? Or did her feet make nary a patter on the town dock as she crept under cover of darkness to a waiting vessel? No one knows how Penelope went about making her escape from Nathanael Cary, the Charlestown sea captain who enslaved her, but some sleuthing can help us understand certain aspects of Penelope’s flight. Clues from the archive shed light on what prompted Penelope to run when she did, why the woman felt particularly justified in seizing her freedom, and what resulted from her stand for liberty.

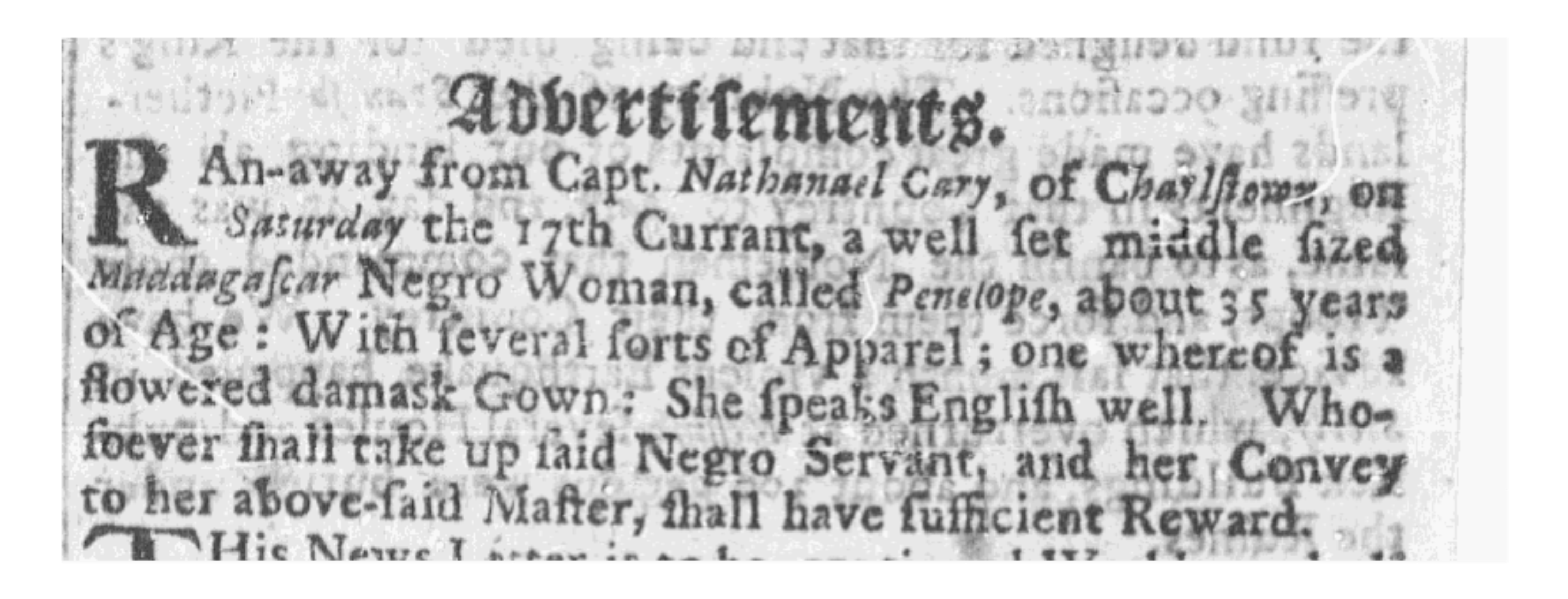

Penelope’s story, to begin with, is a story of firsts. The woman was likely brought to Massachusetts on the first ship to deliver a sizable cargo of Africans to the colony.[1] And when she fled years later, the notice her enslaver posted in attempt to reclaim her was the first newspaper advertisement printed in England’s American colonies for the purpose of capturing a bondsperson of African descent.[2] The woman’s escape, that is, spurred her enslaver to post a notice that inaugurated a genre in the Americas.[3] Tens of thousands of like advertisements would follow the one describing Penelope.

These notices announced far and wide the flight of people in slavery, but only rarely is it possible to learn what resulted from bondspeople’s brave bids for freedom. It was not typical, after all, for enslavers to follow up in print by celebrating captures or deploring fruitless searches. In Penelope’s case, however, other sources help us fill out the story. Records filed in the local court show that Nathanael’s advertisement was successful: Penelope was caught. But they also show that the woman was resolute in her determination to gain liberty. In December of 1705, a year and a half after she had first sought to free herself from her enslaver’s clutches, Penelope took a second stand for freedom. She marched to the courthouse and lodged a complaint against Nathanael for wrongly enslaving her.[4]

In the process of suing Nathanael, Penelope told her story—or, at least, she told parts of it. Listening carefully, we can hear echoes from as far back as 1691, when the woman was in her early twenties.[5] Penelope by this time had developed an intimate relationship with a free man of African descent named Thomas Sungo, who was determined both to marry her and to liberate her. Thomas had allies in this quest: A white neighbor later recalled going to Nathanael’s house to “Assist” Thomas “in a Contract” he was making with Nathanael “Concerning his Negro Woman named Penelope.”[6]

Thomas agreed in this contract to apprentice himself to Nathanael for four years. Nathanael in return would allow Thomas to marry Penelope, and he would set the woman free at the end of Thomas’s term. Any children Penelope bore during the four years would be required to labor for Nathanael for a time—but they would not become chattel slaves.[7] The agreement had some benefits, but it also had downsides. For instance, as Thomas’s neighbor put it, Thomas “would have no advantage with respect to the freedom of his Intended wife, If he should serve 3 years and ¾.” When Thomas pointed this out to Nathanael, though, the enslaver stated that he was “not Willing to [consider] any other termes.” Persuaded that there was no alternative, Thomas complied with Nathanael’s demands.

And so, Thomas relinquished his independence, moved into Nathanael’s household as a bound laborer, and married Penelope. This was an extraordinary stroke of good fortune for the young woman: As a result of the contract, Penelope could look to a future in which she and her husband would be unencumbered by enslavers and able to raise children in liberty.

But then, Thomas died.

Did Thomas die three and three-quarters years into his contract with Nathanael, as he and his neighbor had feared? No record notes the time of Thomas’s passing, but we know that he was gone before Penelope sued for her liberty in 1705 because the court referred to the woman as the “Widow of Tho[ma]s Sungo of Charlestowne.” We also know that Penelope declared herself “ready to prove that ye Condicons of her freedome were Complyed with.”[8] This suggests that Thomas indeed served out his four years. Significantly, Nathanael did not dispute Penelope’s account in court.

But the story does not quite add up. If Thomas had labored the required four years, Penelope should have been freed when those years came to a close, back in 1695. Why would she have waited until 1704 to leave?

A fragment in the archives might provide the answer. In April of 1704, a “Negro ch[ild]” bound by a man identified as “Mr. Cary” passed away.[9] The child’s name is not noted in the record. Nor is the child’s parentage. But both the April 1704 death and the obligation to a man with Nathanael’s last name fit Penelope’s story. Penelope did not desert Nathanael’s household until June 1704, two months after the child claimed by “Mr. Cary” passed away. Perhaps the woman chose to labor in Nathanael’s household while her offspring came of age in bondage, trading her freedom for proximity to the one she cared about—just as her husband had done for her years before.

Whatever Penelope’s motivation for delaying her departure from Nathanael’s household, by 1705 the woman was arguing for her freedom before a jury of her townsmen. This she did with impressive success. The woman’s neighbors, some of whom were enslavers themselves, found that Penelope “is and ought to be a free Womman.” Nathanael, as the losing party, was required to cover Penelope’s legal costs. It was a sweet victory—but a fleeting one. Nathanael did not accept the ruling. He appealed to the colony’s high court, which decreed that Penelope’s suit had been filed in the wrong court. The original decision was reversed.[10]

This devastating reversal provides us with our final glimpse of Penelope’s life.[11] What happened next? Did Penelope run again when the courts failed her? Did she manage to work out an arrangement with her hardheaded enslaver? Or did she live out her life, widowed and perhaps childless, in bondage?

The records do not say.

View References

[1]Described by her enslaver as a “Madagascar Negro Woman,” Penelope likely arrived in Massachusetts 1678, when a local vessel brought 45 Malagasy captives to port. Massachusetts was rarely the destination for more than a few African bondspeople at a time, so this unusual delivery stood out. The governor of the colony recalled in 1680 that “There hath been no Company of blacks or Slaves” brought to Massachusetts except on “one small Vessell” hailing from Madagascar two years prior. This ship carried “betwixt Forty and fifty” Malagasy captives, most of whom were women and children. For Penelope’s description, see “Ran-away from Capt. Nathanael Cary,” Boston News-Letter, June 26, 1704. For the 45 captives, see Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, 25151. For the governor’s report, see Elizabeth Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1932), vol. 3, 14.

[2] For a description of Penelope’s advertisement as the “oldest surviving runaway slave advertisement in a newspaper in the English Caribbean or North American colonies,” see Simon P. Newman, Freedom Seekers: Escaping from Slavery in Restoration London (London: University of London Press, 2022), xxix. The Boston News-Letter was the earliest newspaper regularly published in the English colonies, and it had been in print for less than two months when Penelope absconded. See Charles E. Clark, The Public Prints: The Newspaper in Anglo-American Culture, 1665–1740 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 71, 73, 78.

[3] Of course, the genre had by this point existed for half a century in London, and it was copied by colonial printers from English newspapers. See Newman, Freedom Seekers.

[4] Penelope v. Cary, Middlesex County General Sessions of the Peace Records, vol. 1692–1722, 171, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts.

[5] I am basing this calculation on Nathanael’s 1704 estimate of Penelope’s age as 35. “Ran-away from Capt. Nathanael Cary,” Boston News-Letter, June 26, 1704. We can figure as well that Penelope arrived in Massachusetts as a child of around the age of 9.

[6] Penelope v. Cary, Suffolk Files case 6876, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts. This white advocate, a Charlestown resident named Seth Sweetser, was the son of the man who had once bound Thomas, which suggests that Thomas in freedom maintained a good relationship with his former enslavers.

[7]The only remaining copy of the contract reads that such a child “shall be a servant to mr Nath Cary” until “he or she be the full age of ___,” but it leaves the age blank. See Penelope v. Cary, Suffolk Files case 6876.

[8] Penelope v. Cary, Middlesex County General Sessions of the Peace Records, vol. 1692–1722, 171.

[9] Robert J. Dunkle and Ann S. Lainhart, comps., Deaths in Boston, 1700–1799 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1999), 1028.

[10] Cary v. Penelope, Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature Records, vol 1700–1714, 183, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts. The Superior Court of Judicature argued that Penelope’s case should not have been heard by the General Sessions of the Peace, calling the matter of Penelope’s freedom “not Cognizable” by that court. The GSP, for its part, had previously chosen to “overrul[e]” Nathanael’s objection to Penelope’s choice of court. See Penelope v. Cary, Middlesex County General Sessions of the Peace Records, vol. 1692–1722, 171. Freedom seekers had more success when bringing their cases before the Court of Common Pleas.

[11] Penelope did not start over by filing the case in the Court of Common Pleas, as did some people in Massachusetts who fought wrongful bondage but mistakenly brought their pleas before the criminal court. See, for instance, Titus’s Petition, Suffolk County General Sessions of the Peace Records, vol. 1725–1732, 116, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts; Titus v. Bill, Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas Records, vol. 1727–1728, 286–287, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts; Titus v. Bill, Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature Records, vol. 1725–1730, 176, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, Massachusetts.