It is quite possible that James Teernon had been born in Africa. The scar on his forehead might have been a ‘country mark’, the ritual scarification practiced by some West African peoples. Furthermore, he was described by Captain Terrence Teernon as a man who “speaks good English,” a form of phrasing commonly used for those whose language of birth was different. If James Teernon was indeed African, then he was one of the very small number of enslaved people who was able to revisit Africa, although perhaps not the region from which he came. James Teernon escaped from his enslaver in November 1760, and he then joined the crew of the Dragon, a ship of about 300 tons that sailed from London some three days before Christmas.[1]

Joining the multi-racial crews of merchant and Royal Naval ships was a relatively attractive option for both enslaved and free Black boys and men in London. Ships were always in need of crew members, and Black people born in West Africa and the Caribbean often had a higher degree of immunity to certain tropical diseases because of exposure during childhood, meaning they were less likely that White sailors to succumb to these diseases and leave ships under-manned. Yet James Teernon’s choice of the Dragon is nonetheless surprising. In the words of his enslaver, James Teernon belonged to him and was quite likely enslaved: the fact that they shared the same name may well have meant that the freedom seeker had belonged to the captain since his boyhood. But the Dragon was a slave ship, and the runaway was finding freedom for himself by volunteering to work on a Middle Passage slave ship. The Dragon took on a cargo of 250 enslaved people, but the surviving records do not reveal where in West Africa these people embarked from. The ship then took these unfortunates to Guadeloupe, where the 208 survivors were sold, before returning to London and dropping anchor in the Thames on 20 September 1761.

It is almost incomprehensible to us that a person who might have endured the Middle Passage could willingly become a member of the crew of a slave ship. Does this reveal the absolute desperation of an enslaved person to escape his enslaver? Or does it suggest that some enslaved Africans accepted slavery as at least somewhat normative, and that while they tried to escape bondage they did not necessarily translate that into an opposition to all slavery. In James Teernon’s case we shall never know.

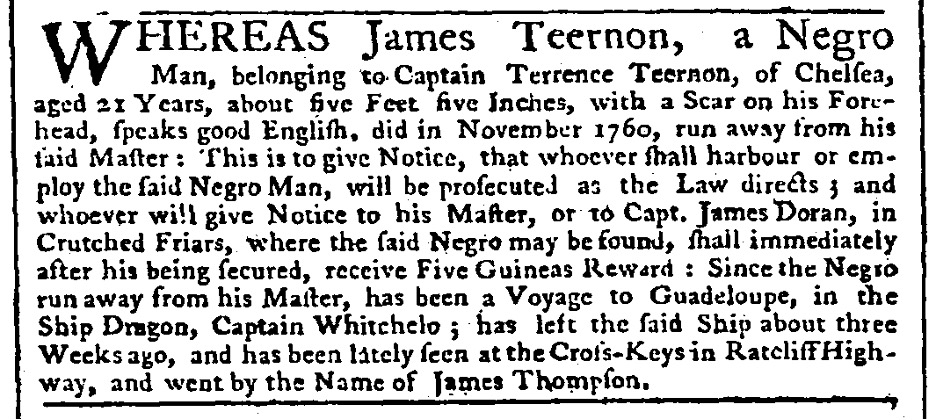

With about six weeks of the return of the Dragon Captain Terrence Teernon discovered that James Teernon had been aboard and was now back in London, spending time at the popular seafaring tavern the Cross Keys in Ratcliff in London’s East End, going by the name of James Thompson. Immediately Captain Teernon placed an advertisement in the Public Advertiser, and the identical advertisement was reprinted on 12 and 14 November. He promised a handsome reward of five guineas for the capture of Teernon/Thompson, who could be returned to him in Chelsea, a western suburb of London some six miles west of Ratcliff. Teernon/Thompson could also be returned to Captain James Doran in Crutched Friars in the City of London, which lay just north of the Tower of London and little more than a half-mile west of Ratcliff.

Doran was an enslaver himself. In fact, one year later, in December 1762, he purchased Olaudah Equiano from Captain Michael Pascal. Doran took Equiano on board of his merchant ship the Charming Sally, which was anchored in the Thames estuary and ready to sail to the West Indies. After Equiano had climbed aboard, Doran told him “you are now my slave,” and after Equiano had protested that he had been baptized and should be free, Doran responded that the unfortunate Equanio “talked too much English; and if I did not behave myself well and be quiet, he had a method on board to make me.” A year later Doran purchased the Wash and the Old Road plantations and enslaved people to work them on Montserrat, and he would die there several years later. Clearly Doran was an enthusiastic enslaver, and would have had no compunction in stripping Teernon/Thompson of his liberty.[2]

But after a year of personal liberty Teernon/Thompson may have proved difficult to catch. Three years later James Thompson, “a Negroe, about 25 years old” was baptized at St Mary, Whitechapel in the heart of London’s East End. In his advertisement in late 1761 Captain Teernon had estimated that James Teernon was about 21 years old: three years later, in 1764, this baptismal record indicated that Thompson was 25 years old. If James Teernon had changed his name to James Thompson, as Captain Teernon indicated in his earlier newspaper advertisement, then this may well have been him.[3] Perhaps born in Africa, enslaved and forced to endure the Middle Passage before being brought to London, the young man had escaped and served in the crew of another slave ship before settling in East London. Perhaps he sailed on other ships, or found other work, and his decision to seek baptism marked at least partial integration into that community.

View References

[1] The Dragon’s voyage (Number 24527) can be found in Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, http://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/24527/variables (accessed 13 August 2017).

[2] Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings, ed. Vincent Carretta (New York: Penguin, 2003), 93-4. See also See “James Doran,” Profile and Legacies Summary, Legacies of British Slavery database, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146665357 (accessed 18 March 2022).

[3] “James Thompson, a Negroe, about 25 years old,” baptismal record, St Mary, Whitechapel, Switching the Lens database, https://search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/300093564?UNIONSEARCH&APPLICATION=UNION_VIEW&DATABASE=LMA_DESCRIPTION&LANGUAGE=144&simple_exp=y&ERRMSG=[WWW_LMA]err.htm (accessed 18 March 2022).