As the name she gave herself after fleeing her enslavers signifies, Free Poll took advantage of the possibilities offered during the American Revolution to declare her own freedom, live with her husband, find paying work, and fashion a life in a growing community of Black Philadelphians, both enslaved and free. Like many freedom-seeking women at the time, she had to calculate the best time and place to achieve those goals. The Revolutionary Era provided greater opportunities, especially for women, to seize their freedom.[1]

Like many enslaved people in Maryland, Free Poll had lived on a large plantation. She was forced to work in the tobacco fields located on a point of land on the Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis. Eight hundred acres in expanse, the plantation contained a brick mansion with thirteen rooms, two kitchens, a chapel, a granary, a farm house, and several barns for drying tobacco leaves. The plantation also included rudimentary wooden shacks, likely built by enslaved people, where Free Poll and other bound people lived. Slave labor created virtually all of the wealth of the plantation for its White owners.[2]

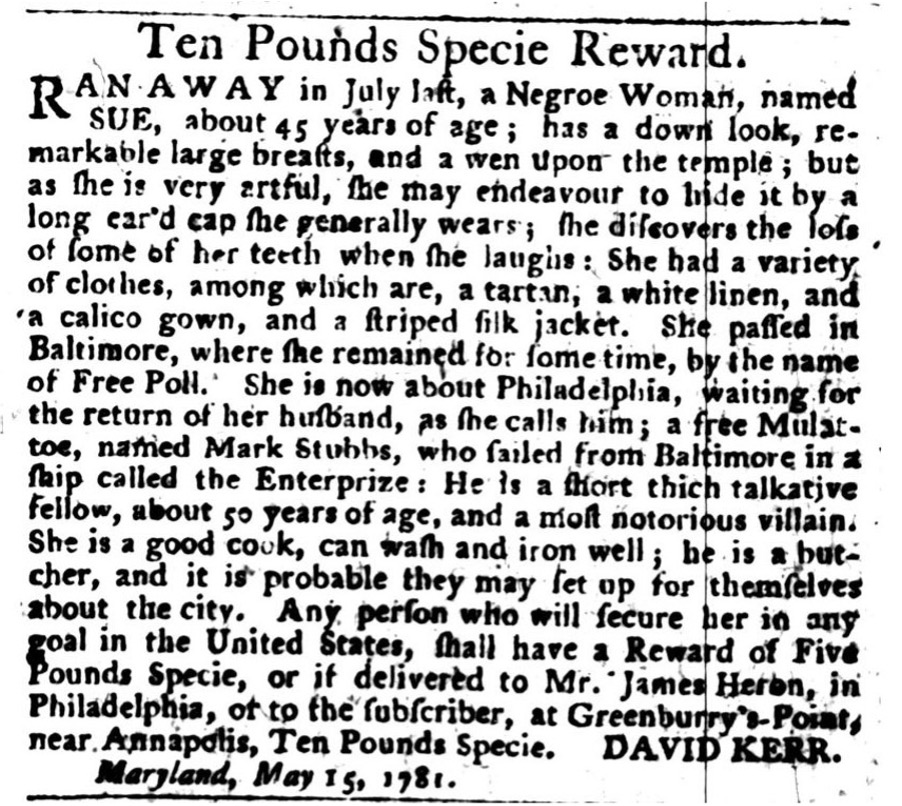

In July 1780, Free Poll surreptitiously fled to the nearest large town, Baltimore. She made the 35-mile journey, perhaps at night, either on foot or on a small boat across the Chesapeake Bay. At the age of 45, she was considerably older than the great majority of escapees, most of whom were young adults.[3] But she shared other characteristics of female fugitives. Many headed for urban centers where they might earn money by doing the sort of work enslaved women often did: cooking, baking pies, and washing clothes. As the above advertisement noted, Free Poll was “a good cook” and could “wash and iron well.” Women freedom seekers also hoped to conceal themselves among other Black people, since many White people did not look closely at nor well remember Black faces. Many escapees also no doubt sought to find assistance and camaraderie, and friends and lovers among other Black residents. Free Poll specifically wanted to join her husband, Mark Stubbs.[4]

About the time of Free Poll’s escape, Mark Stubbs was a mixed-race free man and a sailor on the Enterprize, a privately-owned ship with a commission from the American government to capture British merchant vessels during the Revolutionary War. According to newspaper reports, the Enterprize successfully apprehended several “prizes,” then sailed them to Philadelphia to sell the ships and their cargoes. It was a dangerous business, but one that sometimes paid off. Like other sailors, Mark Stubbs probably received a small portion of the profits, perhaps enough to support himself and his wife for a short while.[5]

After living as a free person in Baltimore for ten months, Free Poll must have learned that Mark Stubbs had returned to Philadelphia, so she made her way there. The City of Brotherly Love contained a growing Black population, some enslaved, some legally free, and others who had fled bondage. Free Poll and Mark Stubbs now lived in Pennsylvania—the first state to pass an emancipation law in the United States, giving encouragement to Black and sympathetic White Revolutionaries that the excessively cruel system of slavery might be on the road to extinction. The law, however, did not grant Free Poll her liberty legally. She would have to remain on guard against re-enslavement by slave catchers for the rest of her life.

Like all advertisements, the notice written by David Kerr reflected the deep prejudices of the enslavers themselves—an important point to bear in mind when we read these advertisements today. He described Free Poll as “artful,” when the likely reality was that she had learned to be clever in dealing with White people. Enslaved people had to pay keen attention to enslavers, who claimed them as property and exercised significant power over their bodies and lives. Those in bondage commonly devised ways to disguise their own feelings to deceive their so-called masters. Not only did David Kerr portray Free Poll as deceitful and cunning, but he also ridiculed her marriage with Mark Stubbs. Since neither enslavers nor the law respected the marriages of the enslaved, David Kerr refused to call Mark Stubbs Free Poll’s husband in his advertisement, referring to him instead as her “husband, as she calls him.”

Modern readers need to be especially suspicious of character descriptions contained in the advertisements. For example, David Kerr characterized Free Poll’s mixed-race husband as a “notorious villain,” probably not based on any of his behavior but rather on his audacity to marry an enslaved woman. What Mark Stubbs wanted was simply to live with his wife. Like all White people who purchased newspaper advertisements, what David Kerr wanted was to re-enslave Free Poll for his own financial benefit. He feared that she and her husband “may set up for themselves” in Philadelphia, meaning that they could enjoy the liberty so ardently sought by White Revolutionaries at the time.

View References

[1] On the increased opportunities for Black women to claim their freedom, see Billy G. Smith, “Resisting Inequality: Black Women Who Stole Themselves in Eighteenth Century America” in Carla Gardina Pestana and Sharon V. Salinger., eds., Inequality in Early America (Hanover, N.H: University Press of New England, 1999), 146-49.

[2] The plantation is described in “To be sold at public vendue,” Dunlaps American Daily Advertiser, March 14, 1795.

[3] Smith, “Resisting Inequality,” 140, 155.

[4] On the ability of female fugitives often to earn money and to hide in cities, see Simon P. Newman, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Escaped Slaves in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica,” William and Mary Quarterly (OI Reader app), June 2018, 1–53. https://oieahc.wm.edu/digital-projects/oi-reader/simon-p-newman-hidden-in-plain-sight-2/ (accessed 1 April 2022).

[5] The Enterprize captured the Nancy, according to a story in the Pennsylvania Packet, September 26, 1780.