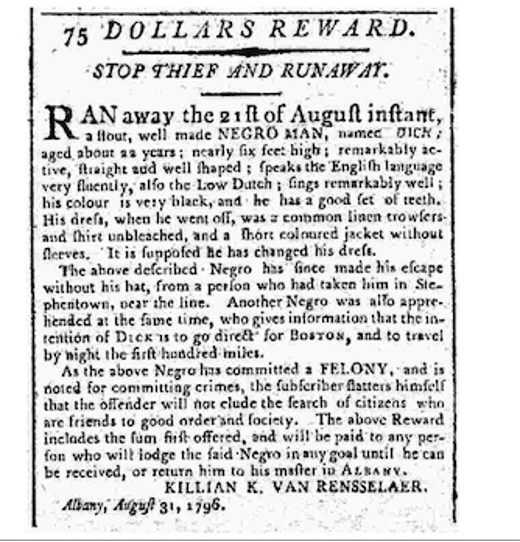

It was an exceptionally hot summer day when Dick fled Albany, New York, in August of 1796.[1] He was hoping to make it to Boston, the capital of neighboring Massachusetts. His escape appears to have been a planned and perhaps coordinated effort. He fled on a Sunday, when his enslaver Killian K. Van Rensselaer attended service in Albany’s Dutch Reformed Church at the intersection of Market and State Street. Dick likely left the Van Rensselaer home on 116 State Street, several blocks uphill from the church, via alleyways and backyards until he got a ride to Stephentown, close to the Massachusetts border. According to a notice in the Albany Gazette, he was joined by Mink, who was enslaved by William Van Arnum just outside of Albany. While their relationship remains unclear, both Mink and Dick were in their early twenties and had a strikingly similar physique.[2]

Mink was apprehended soon after their initial escape, but Dick managed to travel about 120 miles east of Albany before he was captured in early October of 1796. According to Mink, Dick had planned to travel by night for the first 100 miles. Day or night, the journey from Stephentown to Boston through the forested mountains of western Massachusetts would have been harrowing. Perhaps he was eventually discovered through the “warning out” system that took notice of any outsiders in New England towns or by bounty hunters.[3] Even though he was eventually apprehended and returned to Albany, that did not end his attempt at freedom. When they entered the city on October 9th, he “made his escape from the person who had him in custody” before he could be handed over to his enslaver.[4] Once again, he successfully escaped Albany, as is evident from the notice in the October 19 edition of the Massachusetts Spy. The records do not reveal if he made it to Boston this time.

When Dick fled Albany, the county had the largest enslaved population of New York State. Like most enslaved Albanians, he likely lived in the cellar or perhaps he inhabited a small garret space of the Van Rensselaer home on State Street, which Van Rensselaer moved into after his marriage to Margaret Sanders in 1791. Enslaved by one of New York’s most prominent Dutch-descended families, he spoke both Dutch and English. Since Dick was one of two people enslaved by Van Rensselaer, a lawyer and politician, he likely performed a variety of jobs for the family.[5] As the family coachman, he would have gained expert knowledge of the city and region, which would have helped his initial escape.

Dick was in his early twenties when he fled Albany, but he had already witnessed the extreme violence integral to the system of slavery from up close. In November of 1793, a fire ravaged several blocks of the city not far from where he lived. Dean, Bet, and Pompey, all enslaved teens, were arrested for starting the fire. Dick undoubtedly knew them. They were about the same age and lived close to each other. Bet, for instance, resided on the opposite side of State Street at number 87, about a block down the street from Dick. They would have seen each other in Albany’s streets. Perhaps they spent time together in the evenings and on Sundays when they created opportunities to escape their enslavers’ surveillance. They also would have celebrated together during Albany’s yearly Pinkster Festival, a much-loved celebration among Black Albanians.

Bet would eventually confess that she, Pompey, and Dean had started the fire, and in the spring of 1794 the three teenagers were all publicly executed on the Pinkster Hill, not far from where Dick lived.[6] The public hangings on the hill that overlooked the town undoubtedly served as a warning to others. No doubt these events affected Dick deeply. And if he had been accused of a felony, as the notice in the Massachusetts Spy suggests, he may have fled when he did out of fear of a similar punishment.

While many of New York’s enslavers forcefully held on to the institution of slavery during the final decades of the eighteenth century, enslaved people in Massachusetts had helped bring about the demise of the institution in that state. Indeed, in 1783, a Massachusetts judge found that slavery was incompatible with the state’s constitution. That did not mean, however, that slavery quickly disappeared in the state or that it welcomed Black freedom seekers from neighboring states. Emancipation in Massachusetts was a process, not a moment.[7] Yet, for enslaved New Yorkers, especially those who did not live far from the state border, Massachusetts became a place of possible freedom, as is evident from the many notices of that period that looked for men, women, and children from New York who were thought to have fled to Massachusetts.

As for Dick, he did not secure his freedom in the 1790s, but he did not give up on his efforts to be free, as an 1803 notice in The Albany Centinel reveals. This time the person looking for him was James Lenex of Bethlehem, New York.[8] Van Rensselaer may have decided to sell Dick after the attempted escapes, or perhaps he no longer needed him now that he served in the U.S. House of Representatives in Washington D.C. It remains unclear what happened to Dick after his 1803 escape, since no known documents mention him. While there are numerous reasons why he may have disappeared from the records, perhaps this silence means that he finally secured his freedom.

View References

[1] While spending time on his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts, John Adams wrote of August 21, 1796: “The hottest day. Unwell.” John Adams diary 46, 6 August 1787 – 10 September 1796, 2 July – 21 August 1804 [electronic edition], Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/.

[2] The Albany Gazette (Albany), September 9, 1796; The Albany Register (Albany, NY), October 10, 1796; The Albany Gazette (Albany, NY), August 26, 1796; The Albany Centinel (Albany, NY), January 18, 1803; Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy, or Worcester Gazette (Worcester, MA), October 19, 1796.

[3] According to Emily Blanck, Massachusetts “towns warned blacks our more than any other population.” Emily Blanck, Tyrannicide: Forging an American Law of Slavery in Revolutionary South Carolina and Massachusetts (2014), 143.

[4] The Albany Register (Albany, NY), October 10, 1796.

[5] Kiliaen K. Van Rensselaer, and the people he enslaved, moved from Claverack to Albany after he married Margaret Sanders in 1791. Both the census of 1790 and 1800 counted 2 enslaved people as part of his household. 1790 U.S. census, Albany County, New York, Claverack; 1800 U.S. census, Albany County, New York, Albany.

[6] “The examination of Net a Negro Female Slave of Philip S. Van Rensselaer Esquire taken the 28th day of November 1793,” 3-4, New York State Library, Albany; The Albany Register (Albany, NY), November 18, 1793; The Albany Register (Albany, NY), November 25, 1793; The Albany Register (Albany, NY), March 17, 1794.

[7] Jared Ross Hardesty, “Disappearing from Abolitionism’s Heartland: The Legacy of Slavery and Emancipation in Boston,” International Review of Social History (2020), 7.

[8] The Albany Centinel (Albany, NY), January 18, 1803.