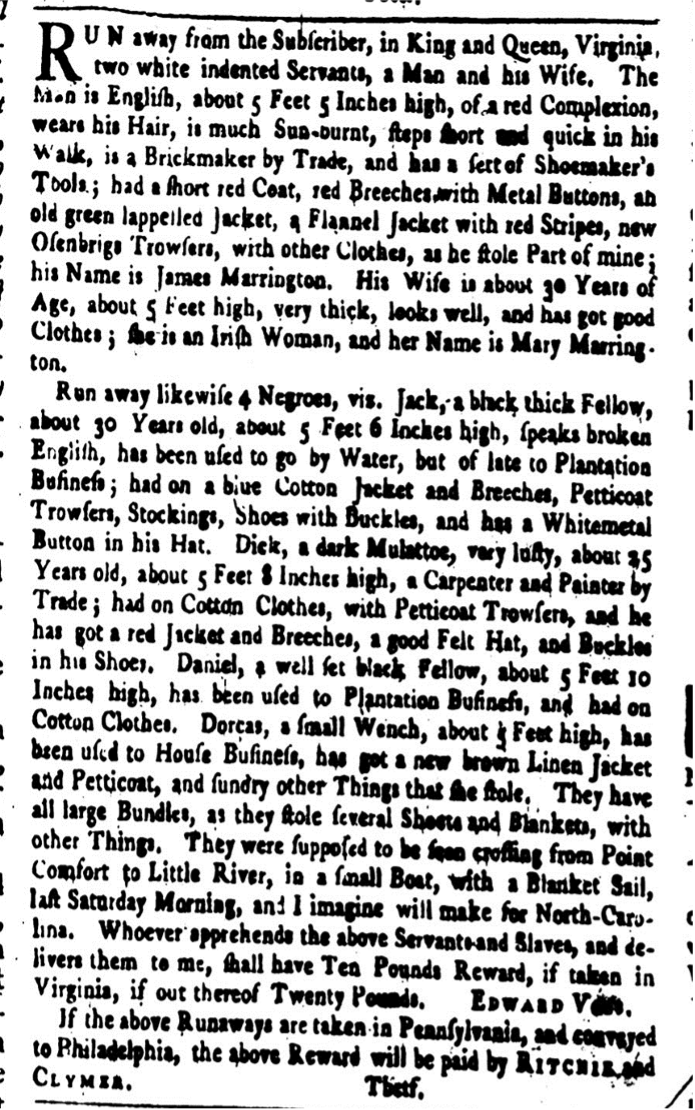

Enslaved Black people and White indentured servants sometimes co-operated in efforts to free themselves. In the Fall of 1764, Jack, Dick, Daniel, and Dorcas organized a well-planned escape with two white bound servants, James and his Irish wife Mary. They took a good many items valuable for their escape, including sheets and blankets with which to construct a sail for a small boat. As a person familiar with navigating the nearby rivers, Jack likely guided the group on that part of their expedition. They may well have been heading for the not-too-distant Great Dismal Swamp in North Carolina and Virginia, as their enslaver surmised, where many refugees had formed maroon societies since 1700, where they lived in relative freedom beyond the reach of enslavers. If they all made it, the five Black people and two White indentured servants likely were welcomed in the mixed-race communities. It would not be easy living in the swamplands, but at least it afforded comparative freedom from Whites who claimed them as property.[1]

Because of the color of their skin and their familiarity with Euro-American cultures, the two indentured servants may not have been as desperate to find haven in the swamps. They enjoyed a much better chance than did Black people of passing as free in predominantly White communities in the British colonies.

Point Comfort, around which the group sailed, ironically was the place of the first documented arrival of enslaved Africans in British North America. In 1619, an English warship, the White Lion, landed with about two dozen captives from the San Juan Bautista, a Portuguese ship carrying African prisoners to be enslaved in Mexico. These people had been captured in the Ndongo kingdom in the interior of Angola, forcibly marched to the coast, and endured the horrific “Middle Passage” across the Atlantic, before being sold into bondage in Virginia. Slavery technically was not legal in 1619 in Virginia, although temporary bondage was. However, during the ensuing decades, White authorities there and in other colonies passed laws defining the permanent enslavement of all Black people.[2]

Scholars have uncovered information about a few of the new, involuntary arrivals from Africa within a few years of 1619. Anthony and Mary Johnson, for example, apparently were sold as indentured servants with limited terms. They worked their way to freedom by the mid-1620s, married, had a child named William, and subsequently became landowners. Their initial legal servitude seemingly resembled that of two of the White freedom seekers, James and Mary Marrington, as described in this 1764 advertisement of their flight. Like half of the migrants from Britain and Europe to colonial America, James and Mary voluntarily signed a contract to work as unfree servants for between three and seven years in return for the payment of their ship passage to North America.[3]

The slavery defined by the White ruling class in Virginia and the other colonies during the 17th century differentiated it from White servitude in three horrifying ways. It was racially based, defining all Black people as property. It was perpetual, lasting a lifetime. And it was inheritable, with the children of enslaved women automatically categorized as enslaved. In economic terms, enslaved Black people lived in poverty. However, the wealth their efforts produced in growing, processing, and marketing tobacco produced tremendous profits for plantation owners and others in White society. Black people created wealth but did not enjoying the fruits of their labor continued for two and a half centuries.

Jack, Dick, Daniel, Dorcas, James and Mary transcended racial differences in hopes of gaining their freedom, perhaps permanently. Like all freedom seekers who fled their purported owners, they faced a daunting task since slavery was legal in every colony in British North America. They apparently targeted one of the few places where they might enjoy the liberty which so many Americans sought during the age of the American Revolution.

While reading these advertisements, it is important to remember that they were written by White people who claimed other humans as property. The notices reflect their perspective rather than the viewpoint of those seeking to escape slavery. We need to take that into account when trying to understand enslaved people who struggled for their freedom. In this 1764 advertisement, for example, Edward Voss clearly recognized the legitimate marriage of two servants as one of the benefits of being White. It is possible that Dorcas may have been wed to one of the three Black men who escaped with her. The lack of any comment about Dorcas’s possible marriage indicated the unwillingness of enslavers to respect marriages and families of enslaved people.

It is also important to be aware of how the meaning of words and phrases have changed during the past few centuries. “Lusty” meant healthy. A “Mullato” was a person of mixed race. Jack not only worked on boats in the rivers in Virginia, but he was also used to “plantation business.” Like most enslaved people in the Upper South, he performed the hard labor associated with producing tobacco, including planting, weeding, harvesting, worming, cutting, and drying. Jack also may have delivered the tobacco in a boat to nearby ships and warehouses. The “house business” in which Dorcas engaged involved every domestic chore her purported owners ordered her to do: cooking, washing and sewing clothes, cleaning, waiting tables, tending the garden, nursing, and caring for White children. It may also have included sexual exploitation by White men.

View References

[1] See Richard Grant, “Deep in the Swamps, Archaeologists Are Finding How Fugitive Slaves Kept Their Freedom,” Smithsonian Magazine (September 2016), available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/deep-swamps-archaeologists-fugitive-slaves-kept-freedom-180960122/ (accessed March 31, 2022).

[2] There are numerous studies about the beginning of slavery in British America. One starting point is information available from the National Park Service, “Historic Jamestown,” https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/african-americans-at-jamestown.htm (accessed March 31, 2022) and https://historicjamestowne.org/history/the-first-africans/ (accessed March 31, 2022).

[3] T. H. Breen and Stephen Innes, “Myne Owne Ground”: Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1640-1676 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).