He called himself Daniel Anderson when he sought refuge from slavery in 1777. He seems to have been calling himself Daniel Anderson for a while, although many of his enslavers called him London. It is unclear what he called himself when he was growing up in the 1750s along Marshyhope Creek, a tributary of the Nanticoke River that straddles the border between Delaware and Maryland and flows into the Chesapeake Bay. As a young person, Anderson was “sold to several masters” throughout the Delmarva Peninsula—newspaper advertisements identify at least four—all the while familiarizing himself with the country’s landscape and its people. He eventually found himself living in a small village where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Susquehanna River, which has since grown into the small city of Havre de Grace.[1]

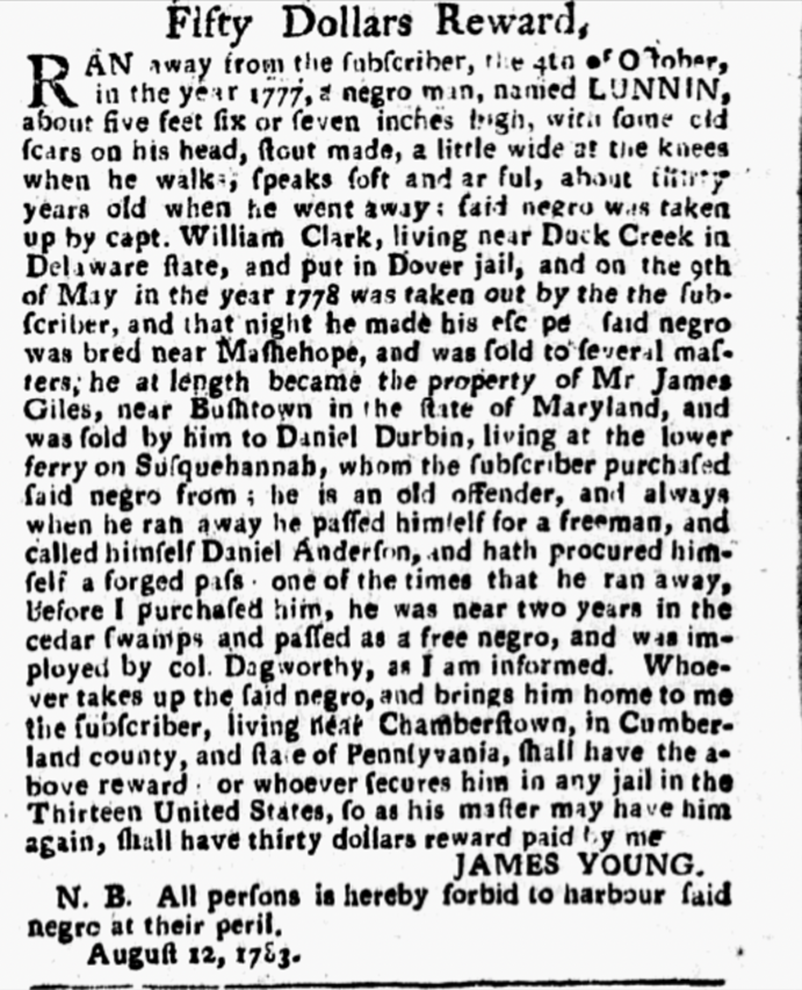

It was during this period of his life that Daniel Anderson began to resist his bondage with regularity and success. His talent for marronage led one of his enslavers to describe him as “an older offender,” noting that he “always” managed to secure a pass when he absented himself. These absences were impressive. Anderson once managed to spend nearly two years in “the cedar swamps” living and working as a free man in the employ of one Col. Dagworthy. Clearly, Anderson understood the fugitive geographies of his corner of the Chesapeake World and its potential as a liberatory landscape.[2]

At some point around the outbreak of the U.S. War for Independence, an army captain named James Young purchased Daniel Anderson and relocated him from Havre de Grace to a farm on the outskirts of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Although this was at least the fifth time enslavers had sold Anderson, it was the first time he found himself so far inland. He did not care for it and decided he would not accept it. On October 4, 1777, one week after Philadelphia fell to the British, Anderson packed his few possessions with scarred hands and left South Central Pennsylvania for Maryland’s Eastern Shore.[3]

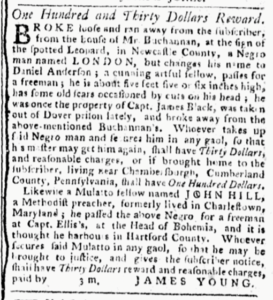

It is eighty-five miles from Chambersburg to Havre de Grace as the bird flies. Since both Pennsylvania and Maryland were slaveholding states when Daniel Anderson set off in the fall of 1777, it is difficult to say with any certainty which route he would have favored. However, it is possible that he would have begun his trek by heading south; the thirty-year-old had a lifetime’s worth of contacts in Maryland and intended to use them. Somewhere near the Susquehanna River he met up with John Hill, a light-skinned Methodist preacher with mixed ancestry who was a free man. The pair traveled east together to the residence of one Capt. Ellis, located at the head of the Bohemia River. There, Hill successfully convinced their company that Anderson was also in possession of his freedom. This allowed the refugee from slavery to pass through the area unmolested and continue his journey home.[4]

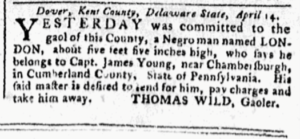

Six months after leaving Pennsylvania, Daniel Anderson was arrested and jailed in Dover, Delaware. A few weeks later, James Young learned about his capture and set off to retrieve him. Young paid Anderson’s jail fees in June 1778 and successfully removed him, but failed to return him to bondage in Pennsylvania. At a Newcastle County tavern a few days’ travel north of Dover, Anderson managed to slip away from Young once more. The army captain was still searching for the self-emancipated man five years later when Britain signed the Treaty of Paris recognizing U.S. independence. It seems Anderson had managed to elude his enslaver for good. Yet this had not stopped Young from registering him as his property on October 4, 1780—exactly three years after Anderson first attempted to seize his freedom—just in case Young ever managed to locate him.[5]

Daniel Anderson was not the only person whom a Pennsylvania enslaver registered as their property in absentia. Indeed, he was not even the only registered refugee from slavery thought to be hiding out in a Delaware swamp! In 1781, a wealthy ironmaster named Peter Grubb offered to pay “One Ton of BAR-IRON” for the return of Abel, a young man who had left his enslaver’s mines in the spring of 1779. “[I]t is supposed he harbours about Apoquinimink in Delaware State,” Peter wrote, “as he has some friends that are freemen living in a cedarswamp in that neighbourhood.” Did Abel and Daniel know one another? What did they make of Pennsylvania’s new abolition law? When Peter Grubb registered eleven people as lifetime slaves in October 1780, he listed Abel last. The Lancaster County clerk noted in his registry that the man had “run away.”[6]

This is not how Pennsylvania’s gradual abolition law was supposed to work. According to the eighth section of the 1780 statute, enslavers had five years to recover the person they claimed to own, at which point they were supposed to bring them “before any two Justices of the Peace” and provide “due Proof, of the former Residence, absconding, taking away, or Absence of such Slave.” Yet this is not what happened. Instead of recovering and properly registering people like Daniel Anderson who sought their freedom during the U.S. War for Independence, enslavers simply registered them in absentia. This practice supplied enslavers with material proof that they owned something—somebody—whom they did not possess. The age of gradual abolition was suffused with these moments of commodification and re-commodification.[7]

Pennsylvania’s abolition program was in part a wartime measure designed to discourage Black freedom-seeking. The same legislation that inaugurated Pennsylvania’s crawl toward emancipation empowered a group of enslavers to turn slave catcher, targeting Black revolutionaries like Daniel Anderson who dared to seize freedom for themselves. Examining Section Eight and the Black Pennsylvanians who made it necessary allows us to reframe the 1780 law as having produced a new kind of slavery regime in the early national north. No matter James Young’s hopes to the contrary, it was a regime that Daniel Anderson did not stick around to experience.

View References

[1] “Dover, Kent County, Delaware State, April 14,” Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, June 3, 1778; “One Hundred and Thirty Dollars Reward,” Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, June 6, 1778; “Fifty Dollars Reward,” Freeman’s Journal, August 27, 1783.

[2] James Young was likely referring to the Great Cypress Swamp and Col. John Dagworthy respectively, as both could be found in Sussex County, Delaware in the 1770s. “Fifty Dollars Reward,” Freeman’s Journal, August 27, 1783.

[3] “Fifty Dollars Reward,” Freeman’s Journal, August 27, 1783.

[4] “One Hundred and Thirty Dollars Reward,” Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, June 6, 1778

[5] James Young registered Daniel Anderson as “Lunnen,” refusing to acknowledge the name that Anderson chose for himself. Although Young’s individual return of Anderson has not been found (which document would perhaps confirm that the enslaver registered him in absentia), we do have the county clerk’s record of his return. The registration in absentia is nevertheless suggested by the fact that Young stated in his 1783 advertisement that Anderson had sought refuge in 1777. See James Young, 1780.045, Slave and Slave Owners Register, Clerk of Courts Records, Cumberland County Archives, Carlisle, PA, https://ccweb.ccpa.net/archives/Holdings?PSID=1819 [accessed May 30, 2024]; “Dover, Kent County, Delaware State, April 14,” Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, June 3, 1778; “One Hundred and Thirty Dollars Reward,” Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser, June 6, 1778; “Fifty Dollars Reward,” Freeman’s Journal, August 27, 1783.

[6] “One Ton of BAR-IRON Reward,” Pennsylvania Gazette, April 25, 1781 as cited in Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisements for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1790 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989), 140; Slaves in Lancaster County in 1780, MG240: African American Records Collection, Series 1: Slave Register, Folder 17: Handwritten Copy of Slave Register, Lancaster History, Lancaster, PA, pp. 30-1. There is no sustained, academic analysis of the experience of marronage in the swamps of the Delmarva Peninsula. In a chapter from his novel about kidnappers and freedom seekers, however, noted nineteenth-century chronicler, George Alfred Townsend, remarked that Delaware’s Great Cypress Swamp was the “counterbalance of the Dismal Swamp of Virginia.” See The Entailed Hat, or Patty Cannon’s Times: A Romance (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1884), 374. For one of the few historical works to identify southern Delaware as a potential maroon community, see the detailed, if dated, study, C. A. Weslager, Delaware’s Forgotten Folk: The Story of the Moors and Nanticokes (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1943), 66-7.

[7] “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” in The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1809: Compiled Under the Authority of the Act of May 19, 1887, compiled by James T. Michell and Henry Flanders, vol. 10 (Harrisburg, PA: Wm. Stanley Ray, 1904), 71-2.