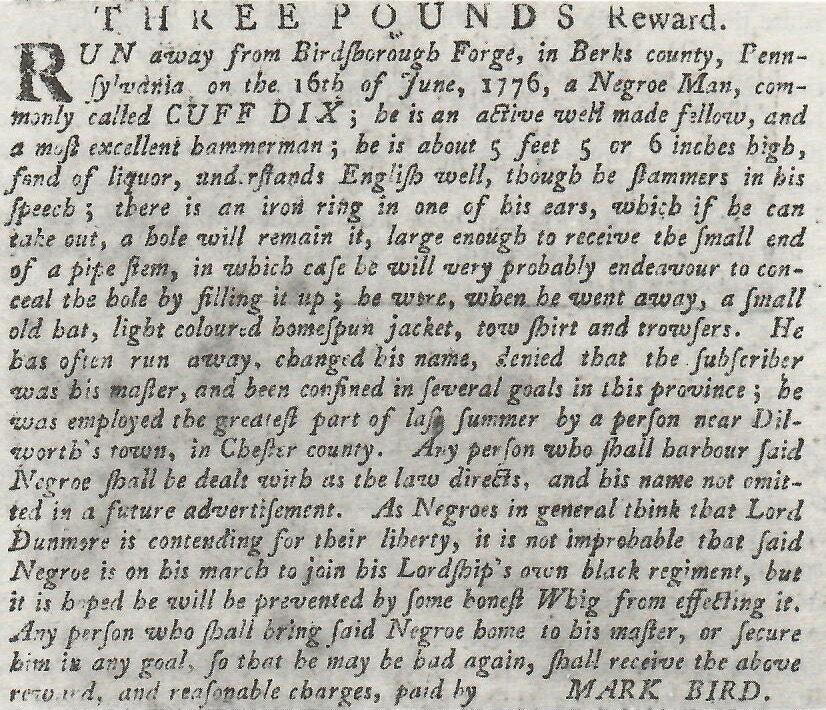

Cuff Dix was determined to be free. Again and again he escaped, even when his enslaver restrained him with collars and chains.[1] But his efforts at self-liberation in the spring of 1775 and again in 1776 were different from an earlier attempt in 1774. Mark Bird, the man who enslaved Cuff Dix, was worried that “As Negroes in general think that Lord Dunmore is contending for their liberty, it is not improbable that said Negroe is on his march to join his Lordship’s own black regiment”. This was the nightmare for enslavers, that the people they claimed as property might join the British army and fight for their own freedom, in essence participating in an armed slave rebellion supervised and supported by the British government. Little wonder that Jefferson’s draft Declaration of Independence asserted that King George III and his servants had “excited domestic insurrections amongst us”, for freedom for the enslaved involved revolution against their enslavers, the Patriots.

Dix would have had good reason to try and make his way south to Virginia. In April 1775 John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore and the governor of Virginia, had first threatened to free and arm enslaved people in the colony and use them to enforce royal authority. On November 7, 1775, he issued a proclamation putting Virginia under martial law and offering freedom to enslaved men who would leave their enslavers and join the British army. Dunmore intended his proclamation to apply only to Virginia, but news of his offer to enslaved people spread through the colonies and was reprinted in newspapers outside of Virginia, including the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser on 6 December 1775. Although Dunmore’s “Royal Ethiopian Regiment” may never have numbered more than about one thousand men, his promise of liberty excited many enslaved people to flee and attempt to make their way to his army. During the first half of 1776 a significant number of enslaved people made their way to Dunmore’s forces, many of them in family groups and some coming from colonies beyond Virginia. By the late spring of 1776 Dunmore’s forces were camped on Gwynn’s Island about 160 miles south of Newcastle, Delaware, as the crow flies. It would have been a difficult journey for men like Cuff Dix, fraught with dangers, and even if he made it the young man was more likely to die of disease: Dunmore believed that he could have rapidly assembled a military force of more than two thousand formerly enslaved men, but smallpox and typhoid laid waste to the small army of freedom fighters.[2]

Cuff Dix was “an active well made fellow, and a most excellent hammerman” in Bird’s forge in Berks County, Pennsylvania. As such he was one of a significant number of enslaved people working for Bird, who owned several forges and furnaces. In 1740 Mark Bird’s father William had built the New Pines Forge on the Schuylkill River about eight miles south-east of Reading and about forty miles north-west of Philadelphia. Under Mark’s direction the Birdsboro Forge became the largest producer of iron during the War for Independence, with a significant enslaved workforce. Bird furnished the Continental Army and the Pennsylvania militia with arms and munitions, and he served as a colonel and quartermaster in the army and was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly.[3]

It is possible that Cuff Dix has been born in West Africa. The name Cuff may have been an abbreviation of the West African day name Cuffee, and the ring in his ear with a large hole may also have been a West African body modification. If African-born, however, he had lived and worked in the colonies for long enough to be fluent in English. The American Revolution provided Cuff Dix and others like him with the opportunity to seize their own freedom, perhaps by joining the British or by establishing a new life for themselves as free men in the new American nation. In October 1776, some four months after his latest escape, Dix was taken into custody and imprisoned in in the Newcastle jail in Delaware, perhaps on his way south to Virginia to join Lord Dunmore.[4]

We cannot be certain that Dix was trying to join Dunmore. But Newcastle, Delaware is about fifty miles south of Birdsboro, and about one-quarter of the way to Dunmore’s final base on Gwynn’s Island. Heading south towards the Chesapeake and plantation slavery made little sense unless Dix was seeking out Dunmore, or perhaps passage on a ship. If Cuff Dix had been aiming to join Dunmore he failed. In early August 1776, two months before Dix’s temporary incarceration in Newcastle, Dunmore had abandoned Virginia and sailed to New York, his force including about three hundred surviving self-liberated African Americans. But this does not necessarily mean that Dix was re-enslaved, for a few days after his capture and incarceration the jailer Thomas Clark published an advertisement announcing that Dix had “MADE his escape from the goal of the county of New-Castle”. This was the last time that Dix’s name appeared in an advertisement, and four years later when Bird listed the enslaved people he owned Cuff Dix was not on the list. This is the last time that we see Cuff Dix, and although he may have died or been re-enslaved, it is possible that he was able to make his way as a free man of colour.[5] And even if Cuff Dix attempt at self-liberation failed he may have inspired others whose bids for freedom succeeded. Seven years later, when the British ship Nisbet sailed away from New York City as the British abandoned the city to the victorious Patriots, one of the many formerly enslaved people on board was thirty-one-year-old Thomas York, a “stout fellow” who was “Formerly slave to Col. Bird Redding, Pennsylvania; [who had] left him in 1777,” just months after Cuff Dix’s escape.[6] In 1775 and 1776, as the spirit of revolution spread across North America, Cuff Dix and Thomas York were just two of the many enslaved African Americans determined to achieve liberty.

View References

[1] “FIVE POUNDS Reward… Will be paid by Mark Bird, for taking up and securing a NEGROE Man, called CUFF… with a Lock and Chain about his Leg,” Pennsylvania Gazette, November 23, 1774; “RUN away the 8th of May, 1775, from Birdsborough Forge, a Negroe Man, named Cuff Dix,” Pennsylvania Gazette, May 24, 1775. A second advertisement indicated that he had escaped with “an iron collar round his neck,” yet had remained at liberty for five months: “SIXTEEN DOLLARS Reward. RUN away, the 8th of May… a Negroe man, named Cuff,” Pennsylvania Gazette, October 11, 1775. He was captured and then incarcerated by Joel Willis, the Chester County jailer, whose advertisement presumably led to Bird reclaiming Cuff Dix: “Chester, November 7, 1775, WAS committed to my custody… Cuff Dicks,” Pennsylvania Gazette, November 15, 1775.

[2] Benjamin Quarles, “Lord Dunmore as Liberator,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. ser., 15 (1958), 494-507; Cassandra Pybus, “Jefferson’s Faulty Math: The Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d. ser., 62 (2005), 248-50.

[3] “RUN away from Birsborough Forge,” Pennsylvania Gazette, July 17, 1776. Birdsboro Steel Foundry and Machine Company records, Philadelphia Area Archives Research Portal, http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/pacscl/ead.html?fq=top_repository_facet%3A%22Tri-County%20Heritage%20Society%22&id=PACSCL_SMREP_TRI07 (accessed March 11, 2022); John Bezís-Selfa, Forging America: Ironworkers, Adventurers, and the Industrious Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), 178-9; Joseph E. Walker, “Negro Labor in the Charcoal Iron Industry of Southeastern Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 93, 4 (1969), 468-9; Daniel A. Graham, Mark Bird, 1739-1812… Ironmaster and Patriot (Elveson, Penn.: Friends of Hopewell Furnace, 2016).

[4] “RUN away from Birsborough Forge,” Pennsylvania Gazette, July 17, 1776; “SIX DOLLARS Reward. MADE his escape from the goal… a Negroe man, named CUFF DIX,” Pennsylvania Gazette, 16 October 1776. For more on Cuff Dix, Mark Bird and forges and slavery in Pennsylvania see Bezís-Selfa, Forging America, 119-120.

[5] “SIX DOLLARS Reward,” Pennsylvania Gazette, 16 October 1776.

[6] Thomas York, “Ship Nisbett, bound for Port Matton, Wilson, Master,” The Book of Negroes—Transcript, Black Loyalist, http://www.blackloyalist.info/sourceimagesdisplaypage/transcript/15 (accessed 14 March 2022). The two-volume manuscript Inspection Roll of Negroes is in the British National Archives, PRO 30/55/100; a second copy of this record can be found in the Inspection Roll of Negroes Book No. 2, Miscellaneous Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, 1765-1821, National Archives, Record Group 360, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5890797 (accessed 14 March 2022).