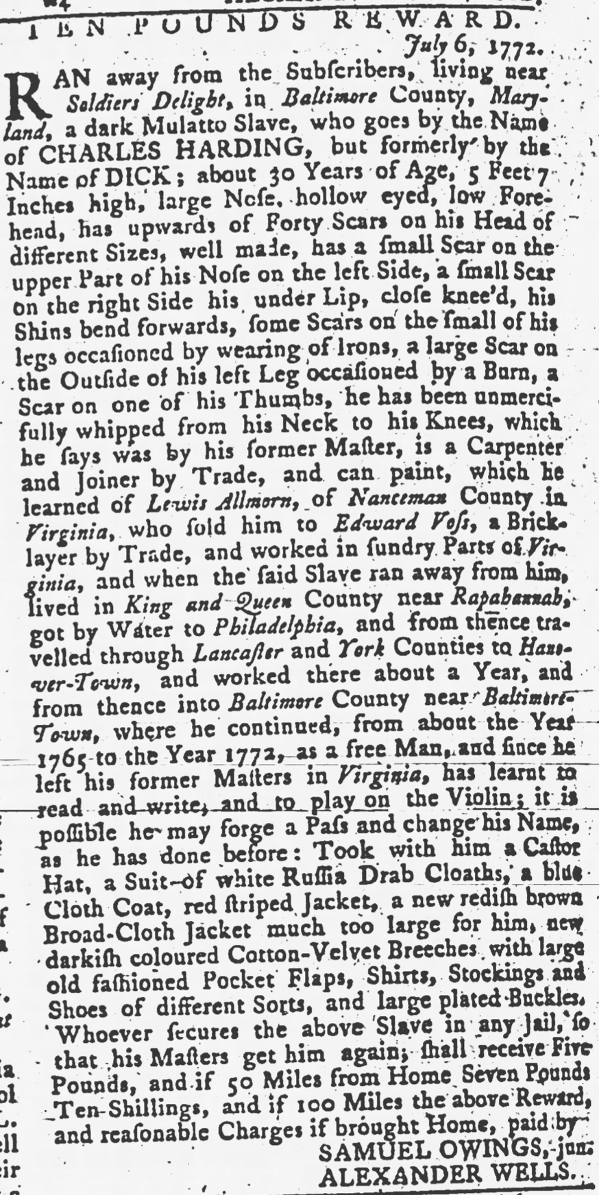

Who was Charles Harding? What kind of man was he, and what kind of life did he have? There is so much that we shall never know, for although he was the subject of at least two advertisements, each around four hundred words in length, Harding is obscured as much as he is revealed by the words of his enslavers.[1] Yet if we allow ourselves to venture beyond this advertisement, to imagine what may have been, we can glean a sense of this remarkable man. With care we can begin to see Charles Harding, looking past his enslavement in order to comprehend the man himself.

The more than forty scars on Harding’s cheeks and forehead indicate that he had enjoyed childhood and adolescence in West Africa, given that these ritual “country marks” were distinctive to people born in Africa and generally marked the bearer’s passage into adulthood. Such an extensive set of country marks indicates that at the very least he had passed into early adulthood by the time that he was enslaved and transported across the Atlantic. If he was about thirty when this advertisement appeared, he may have spent only a little over one-third of his life in North America. Harding knew his African name, and the places, people, and culture of his birthplace still shaped him. Perhaps this musical man hummed the songs and music of his youth. He likely could call to mind the smells of food, the sounds of conversation and laughter, and the vibrant, joyful colors of West African clothing. Reminders of what he had lost, these memories might have existed uneasily alongside Harding’s drive to develop himself and his skills in North America, his embrace of his life as a free man in this environment, and his determination to make the most of the harsh new realities he confronted.

Beyond the bounds of this advertisement, we can begin to imagine a man who was proud, skilled and strong, who embraced life and lived it to the fullest degree possible. No matter how hard successive enslavers strove to break his spirit, Harding stayed true to himself. The admission that Harding had been “unmercifully whipped” and scarred by shackles was—in a runaway advertisement—an admission of failure, for he appears to have spent most of his time in Maryland and Virginia living free, and the advertisement proved that he was once again free. If Harding had been in North America for perhaps twelve years or so, he had been at liberty for at least seven of those years. And Harding had worked to create a new and full life for himself during those years of freedom. He had learned to read and write, and to play the violin, perhaps reviving a musical skill he had first developed in Africa or learning it anew. A second advertisement—published one month later in Philadelphia—added the intriguing detail that Harding had learned Dutch while living free, perhaps indicating that he had spent time in a Middle Atlantic Dutch-speaking community, or even working aboard a Dutch ship. A cosmopolitan, educated man, Harding had learned two European languages, and he likely remembered much of his African language. He dressed himself with the pride of an independent free man, wearing velvet breeches, brightly colored jackets and coats, a stylish castor hat, and even shoes with large and shiny buckles.[2]

Following his escape in 1765, Charles Harding had refused to spend his time living in fear on the margins of White society. Instead, he had seized his opportunity to fashion a full and free life for himself, likely utilizing his experience as a carpenter and painter to make his way, perhaps moving from time to time in order to take up new opportunities. Literacy would have enabled him to participate more fully in society, and perhaps he developed connections and even friendships with Black and White people alike.

The tone of this advertisement suggests that Owings and Wells respected Harding, admiring his ability to rise above the violence inflicted upon him and to free himself and fashion an independent life. He was a man who demanded respect. A month after his escape, Harding remained free, and by advertising in a Philadelphia newspaper his enslavers acknowledged that he had probably traveled a good distance from them. The later advertisement specified higher rewards depending on where Harding might be recaptured: £10 if 100 miles away, rising all the way to £30 if 500 miles distant. Clearly Owings and Wells did not under-estimate Harding, and their second advertisement described him as “a great rogue, [who] stole a good deal of cash, and is artful in making his escape when apprehended.”

A “great rogue.” Perhaps, but it is not these enslavers’ assessment of Harding that echoes down across the years. Rather, it is Harding himself. The scars from the whips and shackles of White enslavers neither restrained nor defined him. He was a proud and able man, a skilled professional who had adjusted from West Africa to North America while steadfastly refusing to submit to enslavement. He demanded freedom and seized it whenever any enslaver tried to detain him, and in freedom he made a life for himself, improving himself and striving to make the most of the opportunities he found. Is it reading too much in the enslavers’ advertisement to imagine Harding free and making music, reading a newspaper and smiling at an advertisement aimed at him, enjoying life, and even laughing? Even though we can never know for sure, we can recognize Harding’s resolute determination to break his shackles, and we can imagine and remember the man who was not a slave.