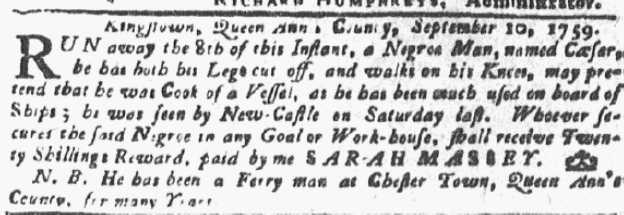

Even more than most freedom seekers, Caesar showed incredible determination to liberate himself. Although he was missing both of his legs, he nevertheless escaped his enslaver, Sarah Massey, and made a break for freedom. Life in places like Chestertown, Maryland, where Caesar was foribly held in bondage, was oriented to the nearby Chesapeake Bay. Although most of the enslaved, both females and males, engaged in hard agricultural labor, a good many others performed work associated with the Bay, sailing small vessels, fishing, and harvesting crabs and oysters—of couse all to the financial benefit of their enslavers.

For a number of years, Caesar operated a small ferry that transported people, animals, tobacco, and other goods across the Chester River. The ferry was a small flatboat that Caesar would pole back and forth across the river carrying cargo. Admirably, Caesar had developed ways to deal with life without legs. Many people in early America, both White and Black, suffered physically from dangerous jobs. Sailors on ships, construction workers, and agricultural laborers not infrequently lost body parts or endured other severe injuries.

Caesar, fed up with life in bondage, apparently decided one day in early September, 1759 simply to allow the ferry to drift thirty miles down the Chester River to the Chesapeake Bay. Having been both a sailor and a Ferry Man, Caesar was comfortable with life on the water. Once on the Bay, he would have had a number of options. Like other fugitives, Caesar may have fashioned a sail out of blankets and sheets that he brought with him.[1] If he were planning either be hired as a cook or to sneak onboard a ship, he might have sailed directly eastward to Annapolis, Maryland, where a number of ships docked.

Many enslaved males who took flight hoped to get on board a vessel, either by stealth or by finding a captain willing to illegally hire a fugitive—undoubtedly at a lower wage than he paid White sailors. Indeed, advertisements for escapees commonly warned that “all masters of vessels are forbid to carry” escapees “off at their peril,” since captains would be breaking the law. For escapees, getting on board a ship was one of best opportunities to gain personal liberty as ships plied the Atlantic Ocean. Some departed the ship when it reached a new port and worked to establish a new life free from bondage.

Caesar made one more appearance in early American newspapers, in 1769, a decade after taking flight from Maryland. He landed in Boston, perhaps after sailing as a free man for a decade.[2] The advertisement described Caesar as “having no legs,” but noted that he was “strolling about the country,” and that a one dollar reward would be paid for his return to the office of the printer of the newspaper. Significantly, the advertisement does not describe Caesar as enslaved or as a bound servant. The small reward offered along with the instructions to return Caesar to the printer’s office suggests that a ship captain had paid for the notice to try to retrieve a sailor who had absconded. Perhaps Caesar was tired of life as a cook on a ship and, like many mariners, took shore leave in Boston and decided not to return to the vessel as it was prepared to sail to another port.

He may also have been attracted by and found support among the vibrant and politically aware Black community in Boston and its environs. At that time, Phillis Wheatly, an enslaved person from West Africa, was writing the first poems published by a Black American. She was keenly aware of the contradiction of many White colonists who sturggled for their freedom while simultaneously supporting the enslavement of Africans.[3] A year after Caesar’s arrival, Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race person of Wampanoag and African and descent, became the first casualty of the American Revolution when he was shot by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre.[4] Meanwhile, enslaved people in Massachusetts actively negotiated for their freedom with people who claimed them as property. They were successful, as enslavement largely ended in the state by 1775.[5]

Hopefully, Caesar lived long enough to enjoy the legal freedom that he had claimed for himself years previously by absconding.

View References

[1] Six enslaved and indentured escapees were seen fleeing “in a small Boat, with a Blanket Sail,” according to an advertisement “Run away from the Subscriber, in King and Queen,” Pennsylvania Gazette, November 29, 1764. See the story based on this advertisement in “Daniel, Dick, Dorcas, Jack, James, and Mary” on this website.

[2] “Caesar a Negro Fellow,” Boston Post Boy, September 4, 1769.

[3] David, Waldstreicher, “Ancients, Moderns, and Africans: Phillis Wheatley and the Politics of Empire and Slavery in the American Revolution,” Journal of the Early Republic 37, no. 4 (Winter 2017), 701–733. https://jer.pennpress.org/media/86416/JER-374-Final-Text-WALDSTREICHER.pdf (accessed 31 March 2022).

[4] See the information from “Africans in America” produced by the Public Broadcasting Series https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2p24.html (accessed 31 March 2022).

[5] Gloria McCahon Whiting, “Emancipation without the courts or constitution: the case of Revolutionary Massachusetts,” Slavery & Abolition 41, no. 3 (November 2019), 1-21.