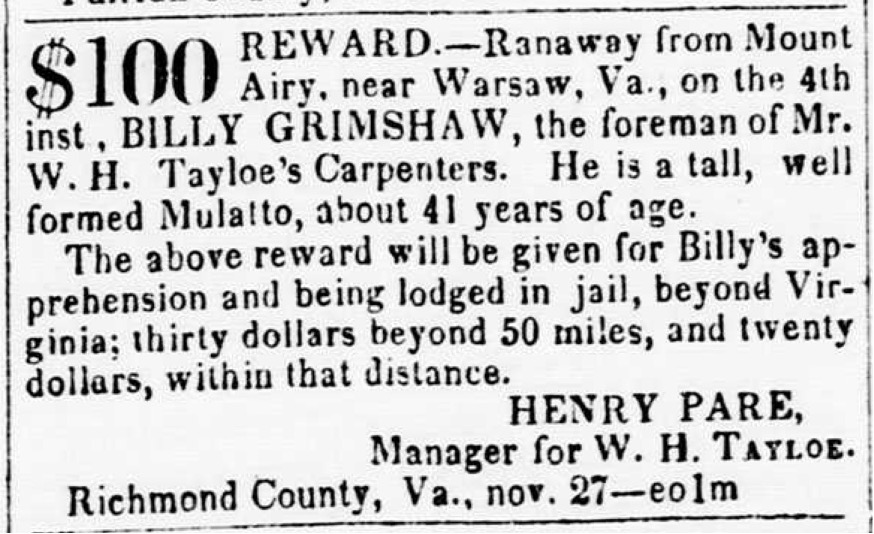

This simple advertisement reveals only that Bill Grimshaw was a “tall, well-formed Mulatto, about 41 years of age.”[1] Grimshaw had been born during Thomas Jefferson’s first term as president, perhaps to Letty and James who were enslaved workers of John Tayloe III at his Neabsco ironworks in Prince William County. In 1820 Tayloe transferred eighteen-year-old Grimshaw to Mount Airy plantation in Virginia’s Northern Neck. At Mount Airy he would work as a carpenter for John Tayloe IV, who was soon succeeded by his younger brother William Henry Tayloe. Within a couple of years Grimshaw had married Esther Jackson, an enslaved textile worker at Mount Airy, and one of three children of the enslaved domestic workers Harry and Winney Jackson. Over the next two decades Bill and Esther had seven children, during which time Bill rose to become Tayloe’s head carpenter, in charge of three other joiners. A skilled craftsman he had twenty-five tools of his own (more than twice as many as the other men), and he alone was entrusted with finished carpentry. His work varied from cutting and making fences, to creating hundreds of barrels for corn, to repairing buildings and equipment around the estate or sometimes at other properties owned by the Tayloe family, including the family home in Washington DC. In short Billy Grimshaw was a skilled craftsman, married with a family, and he was trusted to travel unaccompanied beyond Mount Airy. Why did he escape?

In the summer of 1845 an altercation between Billy Grimshaw and a White overseer resulted in Grimshaw being flogged. This kind of violence was unusual at Mount Airy, particularly for a well-regarded craftsman like Grimshaw. This proud man was so incensed that he took the most radical step available to him, and in November he escaped. William Henry Tayloe paid $3.75 to have an advertisement appear daily in the Alexandria Gazette for a month, but to no avail. Billy Grimshaw had disappeared. We do not know whether he headed north on foot, or if he immediately sought passage or work on a coastal vessel, but Tayloe’s own surviving papers reveal that Grimshaw eventually made his way to Canada where he settled in Saint John, New Brunswick. In the late 1840s and early 1850s Grimshaw had an abolitionist named William Francis write letters on his behalf to William Henry Tayloe. Perhaps Grimshaw had been working and saving, or perhaps he could call on the financial resources of abolitionists like Francis, for in these letters he asked “for what amount you will give him a bill of sale of his body, that he may be at liberty to go or come where his business may call him.” Grimshaw had secured his own freedom but now wanted to legalize his status. He justified his request by noting that “he never should have run away from you if he had not been whip’t, for in no other way had he the slightest reason to complain.”[2] There is no record of Tayloe replying to these requests or granting Grimshaw’s request, and after this final letter dated August 14, 1851 Grimshaw disappeared from view.

Like many enslavers William Henry Tayloe was determined to discourage escape. Allowing Grimshaw to purchase his own freedom after he had escaped would, in Tayloe’s mind, have encouraged others to emulate the self-liberated carpenter. But Tayloe’s determination to prevent future escapes extended beyond ignoring Billy Grimshaw’s letter, and Grimshaw’s family paid a heavy price for the carpenter’s escape. In his next inventory of the estate and enslaved people Tayloe wrote these chilling words next to the names of the Grimshaw family: “Sent this family away for misconduct of the parents.”[3] This suggests that Tayloe believed that Esther had in some ways aided and abetted her husband in his escape: perhaps she had concealed his absence for long enough to enable him to get far away from Mount Airy, or perhaps she had prepared clothing, food and in other ways equipped him for his flight.

The punishment was sure, and it was harsh. Because of Billy Grimshaw’s escape, Tayloe separated and sold each member of Billy Grimshaw’s family, deliberately tearing the family apart and making clear to all others what would happen if anyone else dared escape. Tayloe sold Bill and Esther’s daughters Anna and Juliet to the Reverend Mr. Ward and Dr. Tyler respectively, while their son James and their daughter Winney and her infant son John were sent to Oakland Estate, the Tayloe’s new cotton plantation in Alabama. A little less than a year after Bill Grimshaw’s escape only his wife Esther and their youngest child eight-year-old Henry remained at Mount Airy. Juliet appears to have dictated a letter to her sister Lizza in which she lamented “you can not imagine how lonely I feel sometimes when I think how our family is scattered, my father I know not where nor how he is whether dead or alive, one sister in Alabama mother at home alone without any of her children with her, and we never hear from you.”[4] Just a few months later the family’s dissolution was completed when Taylor finally sold the final members, Esther and Henry. Esther had been unwell and Taylor sold the two for the low price of $300, noting by their names “Sold, or rather given away.” For him it was not about money or profit, but rather punishment for Bill’s escape and a warning to all others who dared imagine that they might be free.

It is tempting to focus on a successful escape, and to justly laud Bill Grimshaw’s determination to free himself, facing down the dangers of navigating through the Upper South and then north to sanctuary in Canada. But there was a heavy price to pay for Grimshaw’s success. The vengeful Tayloe set about destroying Grimshaw’s family, tearing her children away from Esther and away from one another. How many more escapes were never even attempted because enslavers like Tayloe successfully created a regime of terror, a climate of fear about what might happen if anyone dared escape?

View References

[1] Virtually all material for this brief essay is drawn from Richard S. Dunn’s magnificent book A Tale of Two Plantations: Slave Life and Labor in Jamaica and Virginia (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014). See hapter 3, “Winney Grimshaw and her Mount Airy Family,” 106-30.

[2] William Francis to William Henry Tayloe, August 14, 1851, as cited in Dunn, A Tale of Two Plantations, 121-2.

[3] As cited in Dunn, A Tale of Two Plantations, 117.

[4] As cited in Dunn, A Tale of Two Plantations, 119.