How quickly resistance could become revolution. In Boston in the Fall of 1773 popular anger at Parliament’s passage of the Tea Act was building, and in mid-December the arrival of the first tea shipments prompted the Boston Tea Party. When Parliament responded with the Coercive Acts of 1774, delegates from twelve colonies would meet in Philadelphia at the First Continental Congress. By that point armed resistance was only months away, independence little more than a year distant.

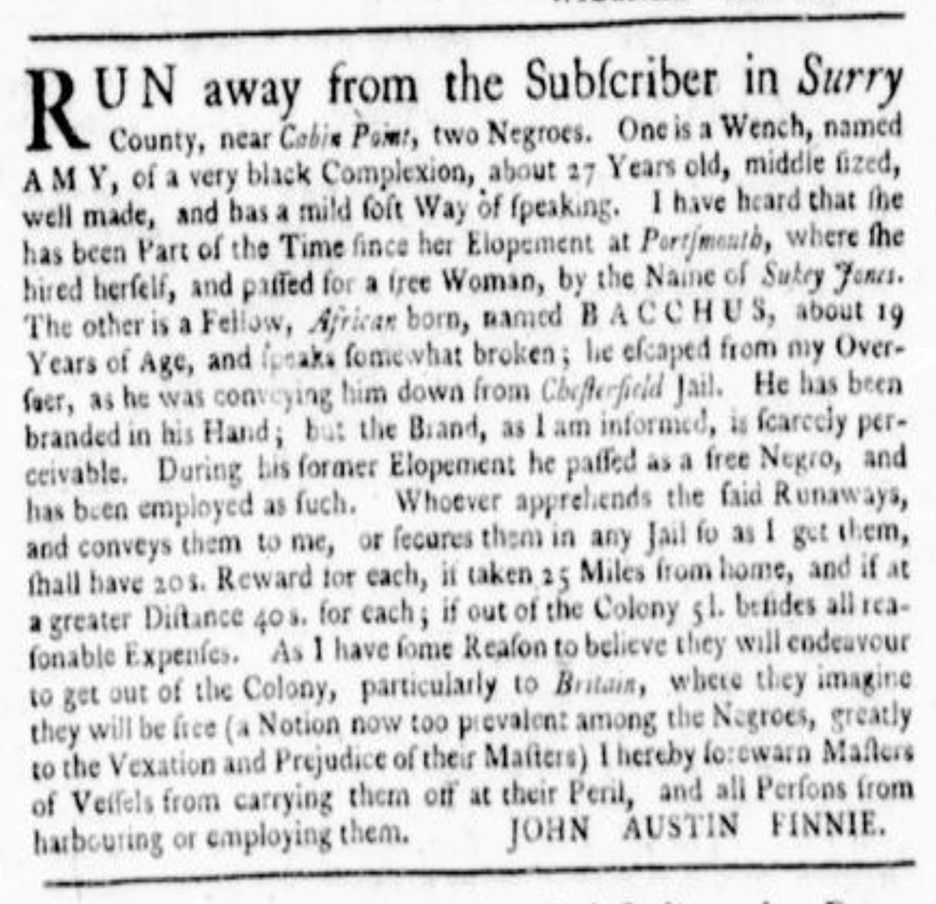

So too at Cabin Point, Virginia, some five miles south of the James River, about midway between Richmond and Norfolk. At some point in September of 1773 the long-term resistance to slavery of Bacchus and Sukey Jones once again turned into rebellion when they escaped from their enslaver, John Austin Finnie. Both had escaped before, passing themselves off as free people. In 1773, however, like the Patriots more than 500 miles away in Boston, Bacchus and Sukey felt a new dawn of freedom. According to their enslaver both were well aware of the judgement handed down by the Court of King’s Bench in London in June 1772 in the case of Somerset v Steuart. The court had ruled that enslavers could not remove enslaved people from England to the colonies against their will, but many enslavers and enslaved people in the colonies interpreted the decision far more broadly as the outlawing of slavery in England. According to Finnie, Bacchus and Sukey would “endeavour to get out of the Colony, particularly to Britain, where they imagine they will be free (A Notion now too prevalent among the Negroes, greatly to the Vexation and Prejudice of their Masters).”[1]

Although only nineteen years old, Bacchus already had a long history of resistance. He had escaped in June 1771, and in the advertisement Finnie placed in the Virginia Gazette his enslaver noted that Bacchus had escaped once before, and that on this occasion he had briefly been recaptured but had then broken free again.[2] But escape had not been Bacchus’s only resistance to enslavement. During these years he struck out hard against slavery, stealing property perhaps to improve his situation, or in an attempt to provide for himself as he endeavored to make himself free, or just because he felt his stolen life and labor entitled him to more. Bacchus first appeared in the Surry Count Court records in January 1771, when he stood in the dock alongside Brother, Amady, Joe, and Phil, enslaved men and a boy who with Bacchus were accused of “Feloniously and Burglariously Breaking and Entering in the Night time the Store House of John Austin Finnie and stealing therefrom Sundry Goods to the Value of Seven Pounds Current Money.” On this occasion Bacchus and Amady were judged to have been innocent and were discharged, while Brother and Joe were sentenced to death, although the court then recommended leniency.[3]

In January 1772 Bacchus again found himself on trial for an unspecified felony. Having pleaded guilty Bacchus was sentenced to death, but for whatever reason this sentence was not carried out. Perhaps he was able to claim benefit of clergy, and the brand that was faintly noticeable on his hand a year later might have been the penalty he paid.[4] Only two months later Bacchus was again in trouble, this time standing accused of “Feloniously and Barglariously Breaking and Entering the Store House of Walter Peter and Stealing thereout a Quantity of Wine of the Value of Twenty Shillings Current Money.” Bacchus pleaded not guilty, and because no witnesses appeared to give evidence against him the court had no choice but to release him. However, “it appearing to the Court that the said Bacchus is a Slave of bad Behaviour, Therefore with the Assent of his said Master, it is Ordered by the Court that he Receive Thirty Nine lashes on his Bare Back at the Common Whipping post for this County.”[5]

A year later, and only months before Finnie advertised for Bacchus and Sukey after their escape, the young man appeared twice before yet another court, this time in Chesterfield County. On July 21, 1773, Bacchus (alias Jemmy, James, or Juba) was arraigned for an unspecified felony. We know this is the same Bacchus, because the court transcript indicates that he was the property of Finnie. Since we know he was African-born, perhaps Juba was his real name, and thus this is the name we should use for him. After examining several witnesses the court found Juba guilty and “demanded of him if he had anything to say why Sentence of Death should not be passed upon him he prayed the Benefit of the Act & to him it is Granted and thereupon he was burnt in the Hand in presence of the Court.” If this was the second time that Juba claimed benefit of clergy he was very fortunate, as in most cases defendants could benefit from this loophole only once. However, the court did not release Juba to Finnie, instead committing him to another trial on the charge of stealing a horse from James Park Fairlie.[6]

Two months later Juba stood before the court once again, although on this occasion there was no mention of the theft of a horse, and instead he was tried for having broken into George Woodson’s house, and stealing clothing to the value of £5. On this occasion the court used only the name given him by his enslaver, Bacchus, and having found him guilty they did not allow him benefit of clergy and sentenced him to death. The court then assessed the value of this healthy young man at £100 “current money,” thus determining the level of compensation that Finnie would receive following the enslaved man’s execution.[7]

The next time that Juba/Bacchus appears in any kind of record was nineteen days later, when Finnie advertised for him and for Sukey in the Virginia Gazette. Somehow the young man had once again avoided the hangman’s noose, and he had escaped from Finnie’s overseer, who had been taking him from the Chesterfield Jail back to Finnie’s plantation.[8] This may well have been the last time that Juba or Bacchus appeared in Virginia records or newspapers, so perhaps on this occasion he, and maybe Sukey too, were successful in making themselves free. The next few years would be chaotic in Virginia as Royal government collapsed, Lord Dunmore encouraged enslaved men to flee and join the British armed forces, and thousands of enslaved people chose freedom. Whatever happened to Juba, this much is clear. He had no respect for his enslaver, or for the property rights of any enslavers. These men had stolen him and thousands like him, and Juba appears to have felt entitled to take whatever he wanted or needed, and to seize any opportunity that he could to escape bondage. From the moment he stepped off a slave ship, Juba had resisted slavery.

View References

[1] “RUN away… AMY… [and] BACCHUS,” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), October 7, 1773. Bacchus is mentioned in Philip D. Morgan, “Slave Life in Piedmont Virginia, 1720-1800,” in Colonial Chesapeake Society, ed. Lois Green Carr, Philip D. Morgan, and Jean B. Russo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 442.

[2] “Cabin Point… RUN away… BACCHUS,” Virginia Gazette, July 4, 1771; July 11, 1771; July 18, 1771.

[3] Court of Oyer and Terminer, January 15, 1771, Surry County, Virginia, County Court, Criminal Proceedings Against Free Persons, Slaves, etc. 1742-1822. MF Reel Number 61, Library of Virginia.

[4] Court of Oyer and Terminer, January 1, 1772, Surry County, Virginia, County Court, Criminal Proceedings Against Free Persons, Slaves, etc. 1742-1822. MF Reel Number 61, Library of Virginia. In medieval England clergymen were able to claim that they were subject to church rather than civil courts, so if accused of a crime in the latter they could claim benefit of clergy and be released. Over time members of the population as a whole could claim benefit of clergy by reciting a passage from the Bible, and receive a lesser punishment (sometimes branding instead of execution), but once branded a person could not again use this loophole. For benefit of clergy in colonial Virginia see Jeffrey K. Sawyer, “Benefit of Clergy in Maryland and Virginia,” American Journal of Legal History, 34 (1990), 49-68.

[5] Court of Oyer and Terminer, March 17, 1772, Surry County, Virginia, County Court, Criminal Proceedings Against Free Persons, Slaves, etc. 1742-1822. MF Reel Number 61, Library of Virginia.

[6] Chesterfield County Court, July 21, 1773, Virginia, Order Book, No. 5, 1771-1774, MF Reel 40, Library of Virginia.

[7] Chesterfield County Court, September 18, 1773, Virginia, Order Book, No. 5, 1771-1774, MF Reel 40, Library of Virginia.

[8] “RUN away… AMY… [and] BACCHUS,” Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), October 7, 1773.