When Pompey Fleet was born in the year 1745, his mother, Venus, could scarcely have imagined the course that her child would chart in life.[1] Pompey would grow up to escape slavery, and then, thanks to his British allegiance in the American Revolution, to escape North America altogether. Ultimately, Pompey would return to the continent from which his ancestors hailed: Africa. Along the way, he would become an accomplished craftsman—but this part Venus might have expected: Pompey’s father, a man who went by the name Peter Fleet, was a gifted woodcut artist who helped run the printing enterprise of Thomas Fleet, the man who held the family in bondage.[2] Peter would train Pompey and his younger brother, Caesar, in a bustling shop just steps from Boston’s State House. The boys were, in the words of one onlooker, “brought up to work at press and case.”[3]They became highly capable as print hands—so capable, in fact, that when their father and enslaver died, one after another, in midsummer 1758, the shop was able to chug along without interruption. Pompey was just 13 at the time; Caesar ten.[4]

Pompey came of age in that print shop. Stooped and ink-smeared, he worked from the grey of dawn to evening candlelight, setting type, inking it, and pressing sheets of paper onto it. Days bled into each other, one to the next, like the ink on a page. But not Mondays. Tasked with delivering the past week’s news to “all the Readers in Town,” Pompey experienced on Mondays the freedom of the streets rather than the confinement of the shop.[5] The young printer traversed every inch of Boston with his papers in tow, making his way from Captain Greenough’s shipyard in the town’s North End to Wind Mill Point on the port’s southern tip. Not surprisingly, Pompey became acquainted with Bostonians of all sorts. As his enslavers put it, the man came to be “well known in Town.”[6]

Taking advantage of his Monday independence, Pompey began to cultivate a friendship with a woman named Cloe Short. Over time, their relationship became serious. In 1773, 15 years after his father’s passing, Pompey, who was still enslaved, and Cloe, who was free, filed with Boston’s town clerk an intention to marry.[7] But an actual marriage did not follow the intention; at least, there is no record that one did. Pompey’s enslavers—Thomas’s sons—appear to have thought little of Cloe. Did they try to stand in the way of the union? Possibly. Something, at any rate, brought Pompey into intense conflict with the Fleets around the time his relationship with Cloe was blossoming, and his enslavers responded harshly: They committed the man to Boston’s Bridewell, a prison-like institution in the town.[8]

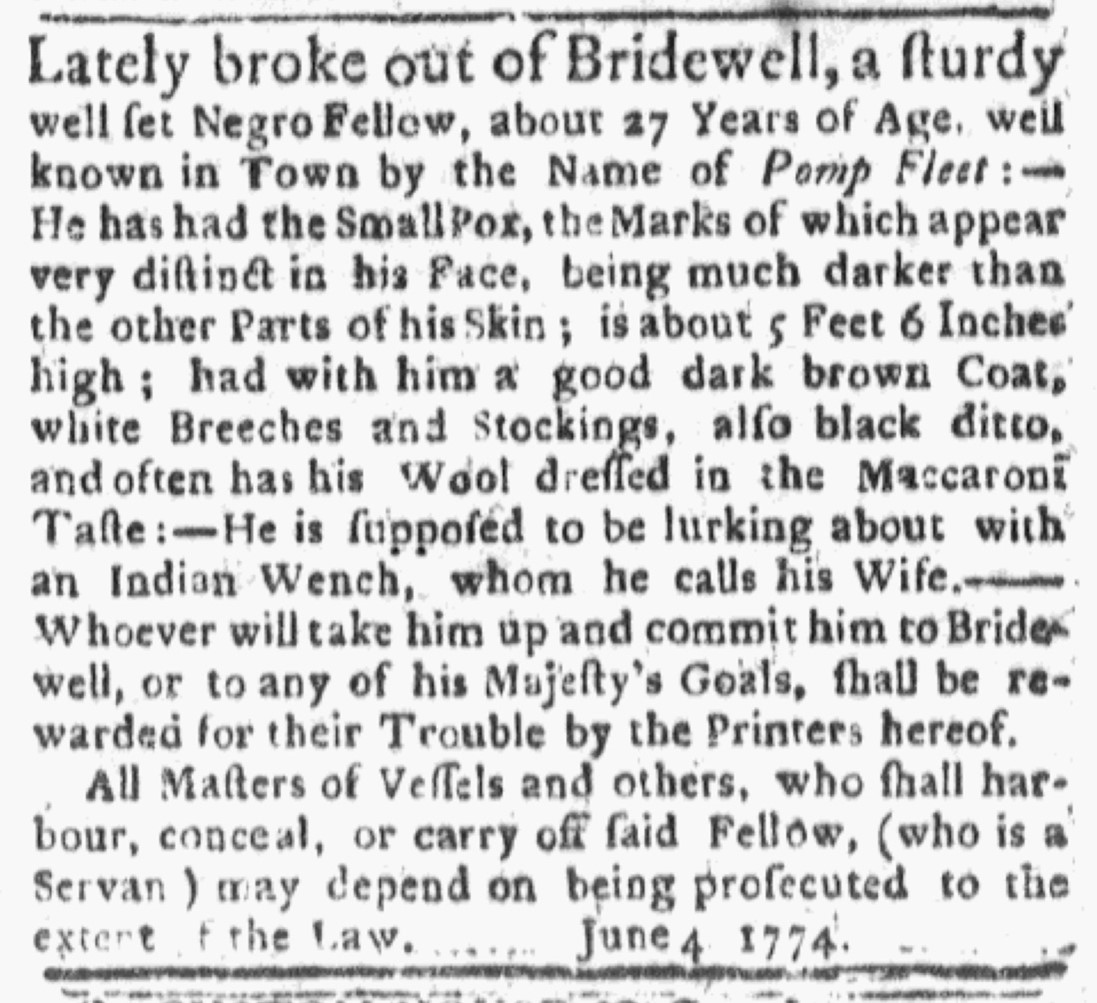

Pompey, though, was not so easily subdued. He managed to escape from the Bridewell, and his enslavers, incensed, advertised for him in their newspaper. “Lately broke out of Bridewell,” they wrote, “a sturdy, well set Negro Fellow, about 27 Years of Age, well known in Town by the Name of Pomp Fleet.”[9] Even though Pompey was “well known,” the printers described him carefully in an effort to ensure his capture. Pompey stood “about 5 feet 6 inches high,” and he “had had the Smallpox, the Marks of which appear very distinct in his Face, being much darker than the other Parts of his Skin.” He was also well-dressed; not only did he possess “white Breeches and Stockings,” but he had a black set of the same, and he carried with him a “good dark brown Coat.”

The printers’ physical description of Pompey is most revealing in the evidence it provides of the man’s pride and sense of self-importance. Pompey’s enslavers reported that he “often has his Wool dressed in the Maccaroni Taste.” Some Black men in the eighteenth century combed their hair up, bunching it high over their forehead, and Pompey fused this inclination with an of-the-moment trend. The “macaroni” style emerged in North America in the 1770s, when wealthy English colonists began to imitate the exaggerated pompadours of Italians, building the foretop of their toupees ever higher. Pompey must have been highly fashion-conscious to incorporate the practice so speedily and to execute it with such flair.[10]

Perhaps the frustrated printers shortened Pompey’s name to “Pomp” in their account of his escape in order to poke fun at the man’s new style and the spectacle of fashion that he had become. No matter. Pompey was doubtless growing comfortable with their censure. He had chosen a partner they scorned: They referred to her as “a wench, whom he calls his wife.” Then he had committed an infraction they deemed worthy of incarceration. Finally, he had tested their patience—and displayed his own cunning—by breaking out of the Bridewell. Pompey’s defiance, though, had only begun.

If the Fleets repossessed the audacious man after his 1774 escape, it was not for long. Pompey joined the British forces at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War and evacuated Boston with them in March, 1776. Together they went to New York City, a bastion of British power and royalist sentiment, where Pompey printed against the American cause under the supervision of loyalist pressman Alexander Robertson. In the end, Pompey’s British allegiance won him his liberty. When the British left New York in 1783, they brought with them some three thousand Black people, most of whom, like Pompey, had deserted rebellious American enslavers to join the British ranks. Pompey sailed alongside Alexander to Port Roseway, Nova Scotia, on a ship with Black loyalists from plantations as far as Georgia and South Carolina.[11]

Pompey continued his work as a printer in Nova Scotia. But his employer died just a year after their arrival, and eventually, tired of low wages and discriminatory legislation, the pressman made preparations to leave.[12] In 1792, he took to the sea once again, this time headed for Sierra Leone, a West African colony founded in large part by Black loyalists.[13] But Pompey did not go empty-handed. He must have found room on the ship for the cumbersome equipment of a printer, for, soon after his arrival, Sierra Leone boasted a press that was “in constant operation.” Transporting these tools—and the knowledge required to make good use of them—was truly an accomplishment: This was the first printing press in Africa south of the Sahara Desert.[14] Pompey had taken his trade from Boston to New York to Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone, printing from slavery to freedom in a world upturned by Revolution.

View References

[1] I calculated Pompey’s birth year based on his age in Thomas Fleet’s inventory. See Thomas Fleet’s 1759 inventory, Suffolk County Probate Records, First Series, vol. 54, 396. No record states explicitly that Venus was Pompey’s mother, but the clues all point in this direction. A contemporary recalled that Pompey was “born in” the house of Thomas Fleet, which means that a woman enslaved in that household must have given birth to him. Venus was the only woman included on the only list of enslaved laborers bound in the Fleet household. And Venus appears to have had a close, spousal connection with Pompey’s father; she was affectionately called “Love” by Pompey’s father in his will, and the man chose to bequeath a share of “all that’s left” of his estate to the woman. For “born,” see Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers (New York: Burt Franklin, 1964[?]) I, 99. For the list, see Thomas Fleet’s inventory, 396. For the will, See Samuel E. Morison, “Will of a Boston Slave, 1743,” Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 25, Transactions, 1922–1924 (Boston: the Society, 1924), 254–254.

[2] Eighteenth-century printer Isaiah Thomas’s autobiographical writings indicate that Peter’s skill was unmatched in his time and place. Isaiah recalled that “scarcely a person in Boston… could cut on wood or type metal” in the mid-1700s, and he regarded Peter’s work as a benchmark by which to judge his own, concluding with satisfaction that his woodcuts were “nearly a match” for Peter’s. Isaiah Thomas, Three Autobiographical Fragments (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1962), 31.

[3] Thomas, The History of Printing, 99.

[4] Three days after Thomas’s death, his newspaper assured readers that the paper would be continued, and “All other printing Business will be carried on as heretofore.” “The News-Paper,” Boston Evening-Post, July 24, 1758. Business indeed carried on as usual; the Fleets did not miss a single issue. As for the paired deaths, Thomas died from a “long Indisposition,” whereas Peter died by drowning; he fell off a fishing boat. The newspaper did not name Peter as the victim of the drowning incident; it merely stated that “A Negro Fellow belonging to [Thomas Fleet]… was drowned.” However, extant evidence suggests that the man was indeed Peter. We know from Thomas’s inventory that Peter no longer belonged to Thomas’s estate at the time the man’s possessions were cataloged. We also know, from a newspaper advertisement, that Thomas owned Peter as late as two months before his death, when he advertised four of his enslaved laborers for sale—one of which was clearly Peter. Therefore, in a fairly narrow window of time, Peter either was sold or died. Clues from the inventory suggest that Peter was not sold. Not only did the extensive account of Thomas’s assets include no cash (which would likely have resulted from a sale), but it listed enslaved people that matched exactly the other three people Thomas had advertised for sale. Therefore, it is clear that three of the four bondspeople Thomas had sought to dispose of prior to his death did not sell. And Thomas’s inability to sell at this time makes good sense; the province’s economy stagnated in the 1740s and 1750s, which resulted in under-employment for the enslaved and a glut of unfree workers on the market. For an account of Peter’s death, see “The Day preceding Mr. Fleet’s Death,” Boston News-Letter, July 27, 1758. For the for-sale advertisement, see “To be sold by the Printer of this Paper,” Boston Evening-Post, May 1, 1758. For the inventory, see Thomas Fleet’s inventory, 396. For the market slump, see Robert E. Desrochers, Jr., “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704–1781” William and Mary Quarterly, 59 no. 3 (July 2002), 658.

[5] “The Publisher of this Paper,” Weekly Rehearsal, Aug. 11, 1735.

[6] “Lately broke out of Bridewell,” Boston Evening-Post, June 6, 1774.

[7] Cloe was recorded as a “negro” in the record of their intention, but other sources complicate her racial identity. She was referred to in the Boston Evening-Post as an “Indian,” and Boston’s Overseers of the Poor called her a “Molatto.” See Boston Record Commissioners, A Volume of Records Relating to the Early History of Boston, Containing Boston Marriages from 1752 to 1800 (Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1903), 434. Also “Lately broke out of Bridewell,” Boston Evening-Post, June 6, 1774. Also Image 197 of 255, “Warning Out Book from 1771 to 1773,” vol. 2, reel 1, Boston Overseers of the Poor Records, 1733–1925, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. Cloe almost surely had some Indigenous ancestry, as she hailed from Grafton, the site of one of John Eliot’s original Indian “Praying Towns.”

[8] Boston’s enslavers used the Bridewell as a place of punishment for their bondspeople. For instance, John Rowe, a Boston merchant who disciplined his enslaved laborers in the mid-eighteenth century, mentioned in his diary: “Last night I sent my negro Cato to Bridewell for a very bad fault.” See Edward L. Pierce, The Diary of John Rowe, a Boston Merchant, 1764–1779 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: John Wilson and Son, 1895), 58.

[9] “Lately broke out of Bridewell,” Boston Evening-Post, June 6, 1774.

[10] For the decision of Black men to bunch up hair on their foreheads, and for the relation of the hairstyles of Black men to European wig wearing and Italian fashion, see Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries” Journal of Southern History 61 no. 1 (February 1995), 55, 58, 60–63, and 66. See also Philip Morgan, Slave Counterpoint (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 604.

[11] Pompey Fleet, described as “short & stout,” traveled to Nova Scotia on a ship called the Three Sisters with Alexander Robertson. Two others traveled under Alexander’s sponsorship: a “small boy” named Sam Fleet and a young woman named Suky Coleman. It is likely that Sam was Pompey’s son, and Suky his spouse. For the travelers, see the “Book of Negroes,” https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/page/?ID=24&Name=Pompey%20Fleet (accessed August 24, 2023). For more on the relationships between them, see J. L. Bell, “The Travels of Pompey Fleet,” Boston, 1775: History, Analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in Massachusetts, https://boston1775.blogspot.com/2014/04/the-travels-of-pompey-fleet.html (accessed August 25, 2023). For a summary of aspects of Pompey’s life at this stage, see Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), 133–134.

[12] For Alexander’s death, see Douglas C. McMurtrie, A History of Printing in the United States (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1936), II, 164.

[13] For Pompey’s departure from Nova Scotia, see the List of Black Indentured Servants who “gave their names for Sierra Leone,” https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/official/indentured_list.htm (accessed August 21, 2023). Suky and Sam went to Sierra Leone with Pompey.

[14] See James W. St. G. Walker, The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 204 and Justin Pope, “A Slave at the Press: Peter Fleet and Reports of Slave Unrest in the Boston Evening-Post, 1735–1758,” Slavery & Abolition 42 no. 4 (2021), 703.