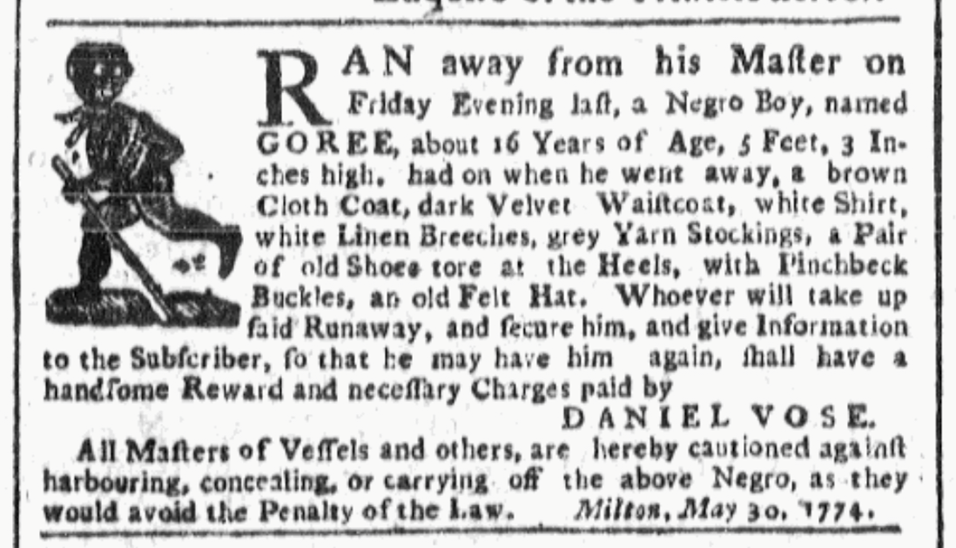

This advertisement appeared in the Boston Post-Boy. The Boston Evening Post and the Essex Gazette also published a copy of the bulletin.[1] Reflecting perhaps the intensity of the moment, reprints appeared in subsequent editions of both newspapers. The story they reveal is a complex one. Whether in the pages of the Boston Post Boy or the Boston Evening Post or the Essex Gazette, the story, partly in black and white, partly in shades of gray, explores the reality of natural rights during an era of American Revolution.

Sometime in May, Daniel Vose paid between “Twelve Pence to Five Shillings” to have the notice printed in the newspapers concerning his disloyal subject. Born in Milton, Massachusetts in 1741, the son of Captain Thomas Vose would grow up to become a prominent leader in town. As extant records would document, he owned a wholesale and retail store and a tavern in town that would also serve as an inn. Through his father-in-law, Jeremiah Smith, he owned perhaps one of the earliest paper mills in New England. He also owned several tracts of land and warehouses in the burgeoning township.[2]

Later, during the escalating conflict between Great Britain and her North American subjects, the Massachusetts businessman would side with the rebels. Like many of his neighbors, he imagined himself not the subject of his King, but his slave. Like many of his fellow New Englanders, he frowned at the crown’s efforts to bully his overseas children. As the crisis grew intense, he volunteered his house as the location where the Suffolk Resolves would be drafted.

But unbeknownst to the tavern keeper, another rebel resided within his house. A recently imported, sixteen-year-old “Negro Boy” from Africa, Goree seized upon the emerging conflict to declare himself free of the tyranny of the king of ales. Approximately four months before his owner met with others privately in a concerted effort to denounce “voluntary slavery,” the African took matters into his own hands. He protested with his feet. When “he went away,” the newspaper advertisements explained, the “5 Feet, 3 Inches” tall young man took with him all of the clothes he wore. To his enslaver’s surprise, he declared his independence.[3]

His clothes, ironically, speak to the peculiar politics of the day. For most were probably made in Great Britain. Although some enslavers “used locally-woven cloth” to clothe enslaved people, Linda Baumgarten observed that “especially around the time of the Revolution, most of the materials for slave clothing in the eighteenth century were imported from England.” Despite the call to produce home spun clothing, many well-to-dos continued to import their wares. Either way, possibly mindful of New England’s cold climes, Goree took an additional coat. Judging from the advertisement Vose had printed in the Evening Post and in the Essex Gazette, Goree had managed to remain at large for well over three weeks. For the return of the fugitive, the tavern owner offered a “handsome” reward of “six dollars.” In this manner, the hunt for the “Negro boy” was afoot; chronicling, ironically, one founding father’s disapproval with his bondservant’s own resolve to be free.[4]

The vignette of the young man’s flight reveals a multi-layered story. Part biography and part autobiography, Goree’s story is one in which he had emancipated himself, fought against the odds, and forged a new life in a New World. Like other fugitives, for example, his name captured aspects of his unique experience in the Atlantic world. A recent arrival, the African-born man was given an impersonal place or pejorative name. While some enslaved Africans had been named Boston, London, or for some other port within the Trans-Atlantic economy, Vose likely named his servant after Goree Island, the door of no return for many African captives, the port island from which New England’s slave traders acquired many enslaved people.[5]

Interestingly, like Venture Smith, whose name can also be traced back to his Trans-Atlantic experience, Goree’s name reflected his painful journey of being brought from Africa to America. Similarly, whilst he was free, Goree might have had a moment to entertain the social and political implications of what Phillis Wheatley, who had been named for the slave vessel that carried her to America, had considered in her best-known verse, “On Being Brought from AFRICA to AMERICA,” wherein she pondered the meaning of her own crossing, a crossing he too would know of all too well:

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.[6]

What he made of it all, that is his life in revolutionary New England, we may never know. We can nonetheless ascertain one thing for sure. When he left, Goree “took away with him” something more than just an ambiguous name. As a matter of fact, the bondservant might have even chosen the name for himself, as a reminder of what he had lost, as a type of symbolic keepsake of what he had endured. In either case, Goree’s flight documented more than letters in black and white. Set in print, his name captures his Middle Passage, a voyage into Orlando Patterson’s “social death,” the transition of a human being made into a commodity or thing, a redemption story in which one founding father is noticeably disturbed by the actions of another founding father and his bid to claim his own natural rights.[7]

View References

[1] Vose had eight advertisements published in four different newspapers for the apprehension of Goree. Boston Post-Boy, May 23, 1774, 3; Boston Evening Post, May 30, 1774, 3; Boston Gazette, May 30, 1774, 3, June 13, 1774, 4; Essex Gazette, May 31, 1774, 172; Boston Evening-Post, June 6, 1774, 4; Essex Gazette, June 7, 1774, 177; Essex Gazette, June 14, 1774, 181.

[2] Boston News-Letter, Monday 17 April to Monday 24 April 1704, 2. Albert Kendall Teele’s History of Milton, Massachusetts, 1640-1887 (Boston: Press of Rockwell and Churchill, 1887), pp. 150, 184, 303, 398-99.

[3] Joseph Warren, At a meeting of the delegates of every town and district in the county of Suffolk: on Tuesday the sixth of September, at the house of Mr. Richard Woodward of Dedham, and by adjournment at the house of Mr. Daniel Vose of Milton, … (Boston: Edes and Gill, 1774).

[4] Linda Baumgarten, “‘Clothes for the People’: Slave Clothing in Early Virginia,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 14.2 (November 1988): 40; Christian Warren, “Northern Chills, Southern Fevers: Race-Specific Mortality in American Cities, 1730–1900,” Journal of Southern History 63.1 (February 1997): 23-56.

[5] William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1988); 6-7; Lorenzo Green, The Negro in Colonial New England (1942; repr., New York: Athenum, 1974), 37-38.

[6] Venture Smith, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself. New London: C. Holt, 1789; Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London: Archibald Bell, 1773), 18. See Vincent Carretta’s Phillis Wheatley Peters: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (University of Georgia Press, 2023) and David Waldstreicher’s The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journeys through American Slavery and Independence (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023) for a fuller account of the poet’s widespread popularity.

[7] For a fuller account of Goree Island and the slave trade, see George E. Brooks’s Eurafricans in Western Africa: Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003).